- Latest articles

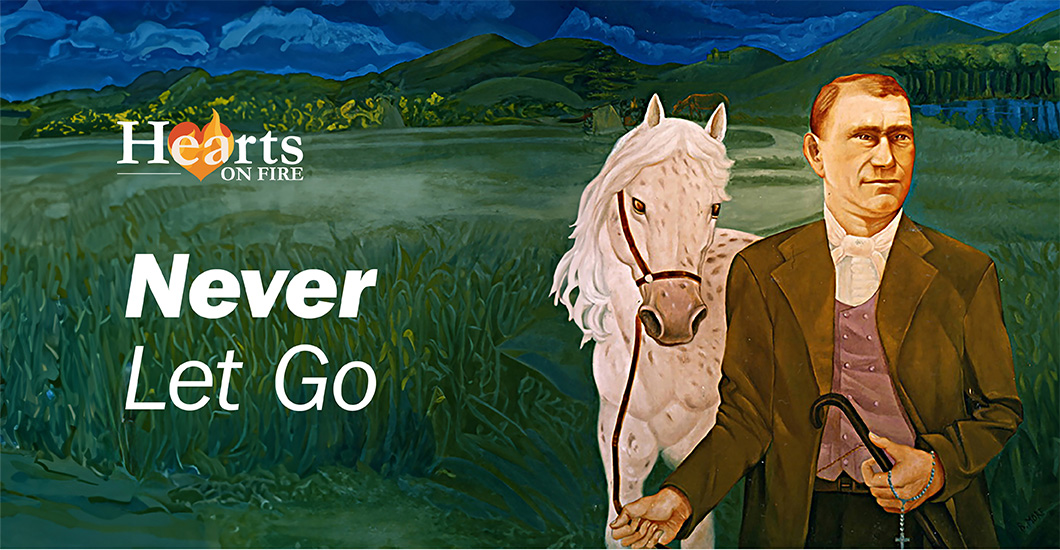

My new hero is Mother Alfred Moes. I realize that she is not a household name, even among Catholics, but she should be. She came on my radar screen only after I became the Bishop of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester, where Mother Alfred did most of her work and where she lies buried. Hers is a story of remarkable courage, faith, perseverance, and sheer moxie. Trust me, once you take in the details of her adventures, you will be put in mind of a number of other gritty Catholic Mothers: Cabrini, Teresa, Drexel, and Angelica, to name a few.

Mother Alfred was born Maria Catherine Moes in Luxembourg in 1828. As a young girl, she became fascinated by the possibility of doing missionary work among the native peoples of North America. Accordingly, she journeyed with her sister to the New World in 1851. First, she joined the School Sisters of Notre Dame in Milwaukee but then transferred to the Holy Cross Sisters in La Porte, Indiana, a group associated with Father Sorin, CSC, the founder of the University of Notre Dame. After clashing with her superiors—a rather typical happenstance for this very feisty and confident lady—she made her way to Joliet, Illinois, where she became superior of a new congregation of Franciscan sisters, taking the name ‘Mother Alfred.’ When Bishop Foley of Chicago tried to interfere with the finances and building projects of her community, she set out for greener pastures in Minnesota, where the great Archbishop Ireland took her in and allowed her to establish a school in Rochester.

It was in that tiny town in southern Minnesota that God commenced to work powerfully through her. In 1883, a terrible tornado tore through Rochester, killing many and leaving many others homeless and destitute. A local doctor, William Worrall Mayo, undertook the task of caring for the victims of the disaster. Overwhelmed by the number of injured, he called upon Mother Alfred’s sisters to help him. Though they were teachers rather than nurses and had no formal training in medicine, they accepted the mission. In the wake of the debacle, Mother calmly informed Doctor Mayo that she had a vision that a hospital should be built in Rochester, not simply to serve that local community, but rather the whole world. Astonished by this utterly unrealistic proposal, Doctor Mayo told Mother that she would need to raise $40,000 (an astronomical figure for that time and place) in order to build such a facility. She in turn told the doctor that if she managed to raise the funds and build the hospital, she expected him and his two physician sons to staff the place. Within a short span of time, she procured the money, and the Saint Mary’s Hospital was established. As I’m sure you’ve already surmised, this was the seed from which the mighty Mayo Clinic would grow, a hospital system that indeed, as Mother Alfred envisioned long ago, serves the entire world. This intrepid nun continued her work as builder, organizer, and administrator, not only of the hospital that she had founded, but of a number of other institutions in southern Minnesota until her death in 1899 at the age of seventy-one.

Just a few weeks ago, I wrote about the pressing need in our diocese for priests, and I urged everyone to become part of a mission to increase vocations to the priesthood. With Mother Alfred in mind, might I take the occasion now to call for more vocations to women’s religious life? Somehow the last three generations of women have tended to see religious life as unworthy of their consideration. The number of nuns has plummeted since the Second Vatican Council, and most Catholics, when asked about this, would probably say that being a religious sister is just not a viable prospect in our feminist age. Nonsense! Mother Alfred left her home as a very young woman, crossed the ocean to a foreign land, became a religious, followed her instincts and sense of mission, even when this brought her into conflict with powerful superiors, including a number of Bishops, inspired Doctor Mayo to establish the most impressive medical center on the planet, and presided over the development of an order of sisters who went on to build and staff numerous institutions of healing and teaching. She was a woman of extraordinary intelligence, drive, passion, courage, and inventiveness. If someone had suggested to her that she was living a life unworthy of her gifts or beneath her dignity, I imagine she would have a few choice words in response. You’re looking for a feminist hero? You can keep Gloria Steinem; I’ll take Mother Alfred any day of the week.

So, if you know a young woman who would make a good religious, who is marked by smarts, energy, creativity, and get-up-and-go, share with her the story of Mother Alfred Moes. And tell her that she might aspire to that same kind of heroism.

'

In the early 1900s, Pope Leo XIII requested the congregation of Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart to go to the United States to minister to the significant number of Italian immigrants there. The congregation’s founder, Mother Cabrini, desired to do a mission in China, but obediently heeded the Church’s call and embarked on a long journey across the sea.

As she had nearly drowned as a child, she formed a great fear of water. Still, in obedience, she…across the sea. On arrival, she and her sisters found that their financial aid had not been sanctioned, and they had no place to live. These faithful daughters of the Sacred Heart persevered and began serving the people on the margins.

In a few years, her mission among the immigrants flourished so fruitfully that till her passing, this aquaphobic nun made 23 transatlantic trips around the world, founding educational and healthcare facilities in France, Spain, Great Britain, and South America.

Her obedience and attentiveness to the Church’s missionary call was eternally rewarded. Today, the Church venerates her as the patron saint of immigrants and hospital administrators.

'

What would you do when a stranger knocks at your door? What if the stranger turns out to be a difficult person?

He says his name with emphasis, in Spanish, with a certain pride and dignity, so you’ll remember who he is—Jose Luis Sandoval Castro. He ended up on our doorstep at Saint Edward Catholic Church in Stockton, California, on a Sunday evening when we were celebrating our patron feast day. Somebody had dropped him off in our relatively poor, working-class neighborhood. The music and the crowd of people apparently drew him like a magnet to our parish grounds.

Unveiling the Truth

He was a man of mysterious origins—we did not know how he arrived at the church, let alone who and where his family was. What we did know was that he was 76 years old, bespectacled, dressed in a light-colored, well-worn vest, and was pulling his luggage by hand. He carried a document from the Immigration and Naturalization Service granting him permission to enter the country from Mexico. He had been robbed of his personal documents and carried no other identification with him.

We set about exploring and discovering who Jose Luis was, his roots, his relatives, and whether they had any contact with him. He hailed from the town of Los Mochis in the state of Sinaloa, Mexico.

Anger, vitriol, and venom spewed from his mouth. He claimed that his relatives had ripped him off and robbed him of his pension in the United States, where he had worked for years, as he went back and forth to Mexico. The relatives we contacted claimed they tried to help him on various occasions, yet he called them thieves.

Who were we to believe? All we knew was that we had a wandering, regular drifter from Mexico in our hands, and we could not abandon him nor put the old, infirm man out on the street. Coldly, callously, one relative said: “Let him fend for himself on the streets.”

He was a man of bluster, bravado, and gruffness, yet he flashed signs of vulnerability again and again. His eyes would water, and he would almost sob as he told how people had wronged and betrayed him. It seemed like he was all alone, deserted by others.

The truth was—it was not easy to help him. He was ornery, stubborn, and proud. The oatmeal was either too chewy or not smooth enough, the coffee was too bitter and not sweet enough. He found fault with everything. He was a man with a gigantic chip on his shoulders, angry and disappointed with life.

“People are bad and mean, they’ll hurt you,” he lamented.

To that, I retorted that there were ‘Buena gente’ (good people) too. He was in the arena of the world where good and evil intersect, where people of goodness and kindness mixed together, like the wheat and chaff of the Gospel.

More than a Welcome

No matter his defects, no matter his attitude or his past, we knew we should welcome him and help him as one of the least of the brothers and sisters of Jesus.

“When you welcomed the stranger, you welcomed me.” We were ministering to Jesus himself, opening the doors of hospitality to him.

Lalo Lopez, one of our parishioners who took him in for a night, introduced him to his family, and took him to his son’s baseball game, observed: “God is testing us to see how good and obedient we are, as His children.”

For several days, we put him up in the rectory. He was weak, spitting out phlegm every morning. It was obvious he could no longer roam and drift freely as he was accustomed to doing in his younger days. He had high blood pressure, over 200. On one visit to Stockton, he said he was hit behind the neck near a downtown church.

A son in Culiacan, Mexico, said he “engendered me” and that he never really knew him as his dad, for he was never around, always traveling, heading for El Norte.

The story of his life began to unfold. He had worked in the fields, harvesting cherries, many years ago. He had also sold ice cream in front of a local church a few years ago. He was, to quote the Bob Dylan classic song, “like one with no direction home, like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone.”

As Jesus left the 99 sheep behind to rescue one stray sheep, we turned our attention to this one man, apparently shunned by his own. We welcomed him, housed him, fed him, and befriended him. We came to know his roots and his history, the dignity and sacredness of him as a person, and not just as another throwaway on the streets of the city.

His plight was publicized on Facebook by a woman who transmits video messages of missing persons to Mexico.

People asked: “How can we help?”

One man said: “I’ll pay for his ticket home.”

Jose Luis, an illiterate man, rough and unrefined, came to our parish fiesta, and by the grace of God, we tried, in some small way, to emulate the example of Saint Mother Teresa, who welcomed the poor, the lame, the sick, and the outcasts of the world into her circle of love, the banquet of life.

In the words of Saint John Paul II, solidarity with others is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of others. It is a reminder that we commit to the good of all because we are all responsible for one another.

'

A one-stop solution to all the problems in the world!

Christus surrexit! Christus vere surrexit! Christ is risen! Christ is truly risen!

Nothing expresses the ecstatic joy of Easter more charmingly than the image of Peter, falling out of the boat in his excitement to reach Jesus. On Easter Sunday, we get the triumphant, even triumphalist declaration of Jesus that we are God’s children now. There is no reaction so ecstatic that it could match the magnitude of the miracle.

Is it sufficient?

The other day, I was discussing all this with one of the wise old monks in our monastery (senpectae, we call them—the ‘old-hearts’). Something he said struck me deeply: “Yes! A story like that makes you want to tell someone about it.” I kept coming back to his phrase: “…makes you want to tell someone about it.” It does.

However, another one of my friends had a different point of view: “What makes you think you’re right about all this? Don’t you think it’s just arrogant to expect that your religion is sufficient for everybody?”

I’ve been thinking about both the comments.

I don’t want to just share this story; I want to convince other people because it’s more than a story. It’s the answer to everyone’s problems. This story is THE GOOD NEWS. “There is no salvation in anyone else,” says Saint Peter, “there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved.” (Acts 4:12) So, I guess I have to admit that I’m right on this one, this news needs to be shared!

Should that strike you as arrogant?

Fact is, if the story of Christ’s Resurrection isn’t true, then my life has no meaning—and more than that, life itself has no meaning because I, as a Christian, am in a uniquely difficult position. My faith hinges on the truth of one historical event. “If Christ is not risen, then your faith is in vain,” says Saint Paul (1 Corinthians 15:14-20).

What You Need to Know

Some people call this ‘The Scandal of Particularity.’ It’s not a matter of whether or not this is ‘true for me’ or ‘true for you.’ It’s a question of whether it’s true at all. If Jesus Christ rose from the dead, then no other religion, no other philosophy, no other creed or conviction is sufficient. They might have some of the answers, but when it comes to the single, most important event in the history of the world, they all fall short. If, on the other hand, Jesus didn’t rise from the dead—if His Resurrection is not a historical fact—then we all need to stop this foolishness right now. But I know He did, and if I’m right, then people need to know.

This brings us to the darker side of this message: as much as we want to share the Good News, and despite the guarantee that it will triumph in the end, we will find, to our immense disappointment, that, more often than not, the message will be rejected. Not just rejected. Ridiculed. Slandered. Martyred. “The world does not know us,” cries Saint John, “just as the world did not know Him.” (1 John 3:1)

Yet what joy it is to know! What joy there is in faith! What joy there is in the hope of our own resurrection! What joy to come to the realization that when God became man, suffered on the cross for our salvation and triumphed over death, He offered us a share in the Divine life! He pours out sanctifying grace upon us in the Sacraments, starting with Baptism. When He welcomes us into His family, we truly become brothers and sisters in Christ, sharing in His Resurrection.

How do we know it’s true? That Jesus is risen? Perhaps it’s the witness of millions of martyrs. Two thousand years of theology and philosophy explore the consequences of belief in the Resurrection. In saints like Mother Teresa or Francis of Assisi, we see a living testimony to the power of God’s love. Receiving Him in the Eucharist always confirms it for me as I receive His living presence and He transforms me from within. Maybe, in the end, it’s simply joy: that ecstatic ‘unsatisfied desire that is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction.’ But when push comes to shove, I know that I am willing to die for this belief—or better yet, to live for it: Christus surrexit. Christus vere surrexit. Christ is truly risen! Alleluia!

'

Wherever you are and whatever you do, you are irrevocably called to this great mission in life.

In the mid-eighties, Australian director Peter Weir made his first American film, a successful thriller, Witness, which starred Harrison Ford. The movie is about a young boy who sees the murder of an undercover police officer by corrupt co-workers, and he’s hidden away in an Amish community for protection. As the story unfolds, he recalls what happened by putting the pieces together and then, he tells the Ford character named John Book (note the Gospel symbolism). The movie contains the marks of a witness: one sees, recalls, and tells.

Circling Back

Jesus showed Himself to His innermost circle so that the truth of His Resurrection would reach everyone through them. He opened the minds of His disciples to the mystery of His Death and Resurrection saying: “You are witness to these things” (Luke 24:48). Having seen Him with their own eyes, the Apostles could not remain silent about this incredible experience.

What’s true for the Apostles is also true for us because we are members of the Church, the mystical Body of Christ. Jesus commissioned his disciples to “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” (Matthew 28:19) As missionary disciples, we testify that Jesus is alive. The only way we can enthusiastically and steadfastly embrace this Mission is to see through the eyes of faith that Jesus is Risen, that He is alive, and present within and among us. That’s what a witness does.

Circling back, how does one ‘see’ the Risen Christ? Jesus instructed us: “Unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.” (John 12:23-24) Put simply, if we really want to ‘see’ Jesus, if we want to know Him deeply and personally, and if we want to understand Him, we have to look to the grain of wheat that dies in the soil: in other words, we have to look to the Cross.

The Sign of the Cross marks a radical shift from self-reference (Ego-drama) to being Christ-centered (Theo-drama). In itself, the Cross can only express love, service, and unreserved self-giving. It is only through sacrificial giving of the self for the praise and glory of God and the good of others that we can see Christ and enter Trinitarian Love. Only in this way can we be grafted onto the ‘Tree of Life’ and truly ‘see’ Jesus.

Jesus is Life itself. And we are hard-wired to seek Life because we are made in God’s image. That’s why we’re drawn to Jesus—to ‘see’ Jesus, meet Him, know Him, and fall in love with Him. That’s the only way we can be effective witnesses to the Risen Christ.

The Hidden Seed

We too must respond with the witness of a life that is given in service, a life that is patterned after the Way of Jesus, which is a life of sacrificial self-giving for the good of others, recalling that the Lord came to us as servants. Practically speaking, how can we live such a radical life? Jesus told His disciples: “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be My witnesses.” (Acts 1:8) The Holy Spirit, just as He did at the first Pentecost, frees our hearts chained by fear. He overcomes our resistance to do our Father’s will, and He empowers us to give witness that Jesus is Risen, He is alive and He is present now and forever!

How does the Holy Spirit do this? By renewing our hearts, pardoning our sins, and infusing us with the seven gifts that enable us to follow the Way of Jesus.

It is only through the Cross of the hidden seed, ready to die, that we can truly ‘see’ Jesus and therefore give witness to Him. It is only through this intertwining of death and life that we can experience the joy and fruitfulness of a love that flows from the heart of the Risen Christ. It is only through the power of the Spirit that we reach the fullness of the Life He gifted us with. So, as we celebrate Pentecost, let us resolve by the gift of Faith to be witnesses of the Risen Lord and bring the Paschal gifts of joy and peace to the people we encounter. Alleluia!

'

Anacleto González Flores was born in Mexico in the late 19th century. Inspired by a sermon heard in his childhood, he made daily Mass the most important part of his life. Though he joined the seminary and excelled in academics, on discerning that he was not called into the priesthood, he later entered law school.

During the years-long Christian persecution in Mexico, Flores so heroically defended the fundamental rights of Christians that the Holy See awarded him the Cross Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice for his efforts. As many Mexican Christians courageously gave their lives for their faith, he continued to write against the atrocities and became a prominent leader of the Cristero War.

In 1927, he was arrested and cruelly tortured—he was flogged, his feet were cut open with knives, and his shoulder was dislocated. An unfazed Anacleto remained firm in his faith and refused to betray his fellow faithful. As he was shot to death, he openly forgave his killers and died, exclaiming: “I have worked selflessly to defend the cause of Jesus Christ and His Church. You may kill me, but know that this cause will not die with me.” He openly forgave his killers and died, exclaiming: “I die, but God does not die. Long live Christ the King!”

After years of living a holy life centered on devotion to the Blessed Sacrament and an exemplary Marian devotion, Flores gave his life to the Lord with three of his fellow faithful. This brave martyr was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, and he was declared the patron of the Mexican laity in 2019.

'

Several years ago, I participated in the annual meeting of the Academy of Catholic Theology, a group of about fifty theologians dedicated to thinking according to the mind of the Church. Our general topic was the Trinity, and I had been invited to give one of the papers. I chose to focus on the work of Saint Irenaeus, one of the earliest and most important of the fathers of the Church.

Irenaeus was born around 125 in the town of Smyrna in Asia Minor. As a young man, he became a disciple of Polycarp who, in turn, had been a student of John the Evangelist. Later in life, Irenaeus journeyed to Rome and eventually to Lyons where he became Bishop after the martyrdom of the previous leader. Irenaeus died around the year 200, most likely as a martyr, though the exact details of his death are lost to history.

His theological masterpiece is called Adversus Haereses (Against the Heresies), but it is much more than a refutation of the major objections to Christian faith in his time. It is one of the most impressive expressions of Christian doctrine in the history of the church, easily ranking with the De Trinitate of Saint Augustine and the Summa theologiae of Saint Thomas Aquinas. In my Washington paper, I argued that the master idea in Irenaeus’s theology is that God has no need of anything outside of Himself. I realize that this seems, at first blush, rather discouraging, but if we follow Irenaeus’s lead, we see how, spiritually speaking, it opens up a whole new world. Irenaeus knew all about the pagan gods and goddesses who stood in desperate need of human praise and sacrifice, and he saw that a chief consequence of this theology is that people lived in fear. Since the gods needed us, they were wont to manipulate us to satisfy their desires, and if they were not sufficiently honored, they could (and would) lash out. But the God of the Bible, who is utterly perfect in Himself, has no need of anything at all. Even in His great act of making the universe, He doesn’t require any pre-existing material with which to work; rather (and Irenaeus was the first major Christian theologian to see this), He creates the universe ex nihilo (from nothing). And precisely because He doesn’t need the world, He makes the world in a sheerly generous act of love. Love, as I never tire of repeating, is not primarily a feeling or a sentiment, but instead an act of the will. It is to will the good of the other as other. Well, the God who has no self-interest at all, can only love.

From this intuition, the whole theology of Irenaeus flows. God creates the cosmos in an explosion of generosity, giving rise to myriad plants, animals, planets, stars, angels, and human beings, all designed to reflect some aspect of His own splendor. Irenaeus loves to ring the changes on the metaphor of God as artist. Each element of creation is like a color applied to the canvas or a stone in the mosaic, or a note in an overarching harmony. If we can’t appreciate the consonance of the many features of God’s universe, it is only because our minds are too small to take in the Master’s design. And His entire purpose in creating this symphonic order is to allow other realities to participate in His perfection. At the summit of God’s physical creation stands the human being, loved into existence as all things are, but invited to participate even more fully in God’s perfection by loving his Creator in return. The most oft-cited quote from Irenaeus is from the fourth book of the Adversus Haereses, and it runs as follows: “The glory of God is a human being fully alive.” Do you see how this is precisely correlative to the assertion that God needs nothing? The glory of the pagan gods and goddesses was not a human being fully alive, but rather a human being in submission, a human being doing what he’s been commanded to do. But the true God doesn’t play such manipulative games. He finds His joy in willing, in the fullest measure, our good.

One of the most beautiful and intriguing of Irenaeus’ ideas is that God functions as a sort of benevolent teacher, gradually educating the human race in the ways of love. He imagined Adam and Eve, not so much as adults endowed with every spiritual and intellectual perfection, but more as children or teenagers, inevitably awkward in their expression of freedom. The long history of salvation is, therefore, God’s patient attempt to train His human creatures to be His friends. All of the covenants, laws, commandments, and rituals of both ancient Israel and the church should be seen in this light: not arbitrary impositions, but the structure that the Father God gives to order His children toward full flourishing.

There is much that we can learn from this ancient master of the Christian faith, especially concerning the good news of the God who doesn’t need us!

'

When a terrible loss led Josh Blakesley into the light, music from his soul became a balm to many bleeding hearts.

Growing up in the small town of Alexandria, Josh was a carefree child.

He grew up listening to his Dad’s music; two elder sisters with a great music collection was a bonus that nurtured his musical taste. Without professional training or theoretical inputs, in an age with no internet and YouTube, Josh had what he would later call ‘a side entry’ into the world of music. Starting on the drums and simultaneously learning to sing, he was enamored by the likes of Don Henley and Phil Collins, following their legendary works through magazines and books.

With his mother, though, Church was a non-negotiable matter. Thanks to her insistence, he went to Mass every Sunday. But he would leave God there and live the rest of his life on a totally different plane.

Diving Deeper

They met in Spanish class when he was 15, and unlike any other 15-year-old, she took him along to a prayer meeting. This was new and different from anything he had experienced before. Teenagers his age were coming together to worship the Lord. This worship experience was modern and engaging…with music, talks, and skits by people his age! He was intrigued, but he wouldn’t have kept coming back every week if Jenny hadn’t asked him to.

Several months later, Jenny was hit by a drunk driver and killed in an accident. Her loss was a huge blow to the entire community. As he struggled with the grief of losing her, it triggered a realization that life here is finite, and there must be purpose in it, a reason that we are living.

From that very moment, he began a journey, searching for answers to the questions that fascinated him…‘What is the reason for me? What is the purpose of what I’m doing right now? Why has God put me on this planet? What’s my role while I’m here?’

He started diving more into why we were here on this planet. In realizing that his gifts were from God, and in searching for a purpose in the use of these gifts, he realized that he wanted to give back to God and return the love.

A Bolt of Realization

He started playing music for Mass and getting involved in the liturgy. As he puts it: “There has been a faith part to my music and a music part to my faith as well. Those are still ingrained. I pray through music a lot”. And it is this experience of prayer that he tries to hand over to his brethren through writing and playing music. The “awesome and overwhelming” experience of leading people into worship and hearing them singing along makes him whisper so often: “The Lord is moving right now, and I don’t have to work.”

Bridging the Gap

Josh is now a full-time singer, songwriter, producer, music director, husband, and dad.

Even while leading the music at Mass every Sunday, Josh knows that Mass can happen without music—what a musician does at Mass doesn’t bring Jesus any greater into the room; He is there regardless. What a musician can do is “elevate the worship of the faithful by bringing some extra beauty through music.” This indeed, is one of his life goals—to try and bridge that gap and bring quality music into the liturgy.

But he doesn’t stop there; in addition to adding beauty to the Sacramental experience, he goes another mile to bring God to the people.

Right from His Heart

As a Catholic musician, Josh writes songs for the Mass and writes from the heart. Sometimes, when it comes out, it might not be out rightly Mass-material, but what comes out is still a tribute to God for the gift of music.

He relates that his song Even in This was such an experience right from his heart.

The Church community he was part of had just lost a teen, and seeing them go through the pain, the tragedy, and the devastation took him back to his own experience of losing a dear friend in his teenage years. Diving into the pain, he wrote that even in these darkest nights, God is with us. In the ‘valleys of pain’, in the ‘shattered, broken things’, in the ‘ hurt you cannot hide’ and the ‘fear you cannot fight’, he reassures his listeners that though you cannot see God, “You are not alone.”

This is one message Josh wants to repeat to the world: “God is moving with you.”

'

We all wrestle with God at one point or another, but when do we really attain peace?

Recently, a struggling friend told me: “I do not even know what to pray for.” She wanted to pray but was growing weary of asking for something that was not coming. I immediately thought of Saint Peter Julian Eymard’s Eucharistic Way of Prayer. He invites us to model our prayer time after the four ends of the Mass: Adoration, Thanksgiving, Atonement, and Petition.

A Better Way

Prayer is more than asking, yet there are times when our needs and worries about our loved ones are so pressing that we do nothing but ask, ask, plead, and then ask some more. We might say: “Jesus, I leave this in your hands,” but 30 seconds later, we grab it right out of His hands to explain why we need it again. We worry, fret, and lose sleep. We don’t stop asking long enough to hear what God might be trying to whisper to our weary hearts. We go around like this for a while, and God lets us. He waits for us to wear ourselves out, to realize that we are not asking Him to help us, but we are trying to tell Him how we think He needs to help us. When we grow tired of wrestling and finally surrender, we learn a better way to pray.

In his letter to the Philippians, Saint Paul instructs us on how we should approach our petitions to God: “Have no anxiety at all, but in everything, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, make your requests known to God. Then the peace of God that surpasses all understanding will guard your hearts and minds in Christ Jesus.” (4:6-7)

Combat the Lies

Why do we worry? Why do we get anxious? Because, like Saint Peter, who stopped looking at Jesus and began to sink (Matthew 14:22-33), we too lose sight of the Truth and choose to listen to the lies. At the root of every anxious thought lies a big lie—that God will not take care of me, that whatever problem worries me now is bigger than God, that God will abandon me and forget me…that I don’t have a loving Father after all.

How do we combat these lies? With the TRUTH.

“We must simplify the work of our mind by a simple and calm view of God’s truths,” reminds St. Peter Julian Eymard.

What is the truth? I like Saint Mother Teresa’s answer: “Humility is truth.” The Catechism tells us that “humility is the foundation of prayer.” Prayer is raising our hearts and minds to God. It is a conversation, a relationship. I can’t be in a relationship with someone I do not know. When we begin our prayer with humility, we acknowledge the truth of Who God is and of who we are. We recognize that, on our own, we are nothing but sin and misery but that God has made us his children and that in Him, we can do all things (Philippians 4:13).

It is that humility, that truth, that brings us to first adoration, then thanksgiving, then repentance, and finally to petition. It is the natural progression of one who is completely dependent on God. So when we don’t know what to say to God, let us bless Him and praise His name. Let us think of all the blessings and thank Him for all He has done for us. This will help us trust that this same God, who has always been with us, is still here today and is always for us through good times and difficult times.

'

It was July 1936, the height of the Spanish war. El Pelé was walking through the streets of Barbastro, Spain, when a huge commotion captured his attention. As he rushed to the source, he saw soldiers dragging a priest through the streets. He couldn’t just stand on the fringes and watch; he rushed to defend the priest. The soldiers weren’t intimidated and shouted at him to surrender his weapon. He held up his rosary and told them: “I have only this.”

Ceferino Giménez Malla, fondly known as El Pelé, was a Romani—a community often pejoratively referred to as Gypsies and looked down upon by mainstream society. But Pelé was held in great esteem not only by his own community, even educated people respected this illiterate man for his honesty and wisdom.

When he was arrested and imprisoned in 1936, his wife had passed away, and he was already a grandfather.

Even in prison, he continued to hold fast to his rosary. Everyone, even his daughter, begged him to give it up. His friends advised him that if he stopped praying, his life might be saved. But for El Pelé, to give up his rosary or to stop praying was symbolic of denying his faith.

So, at the age of 74, he was shot dead and thrown in a mass grave. This brave soldier of Christ died shouting: “Long live Christ the King!” still holding a rosary in his hands.

Sixty years later, Blessed Ceferino Giménez Malla became the first of the Romani community ever to be beatified, proving again that the Savior is ever-present to everyone who calls upon Him, irrespective of color or creed.

'

Scared and alone on a boat in the middle of a stormy sea, little Vinh made a bargain with God…

When the Vietnam War ended in 1975, I was still a child, the second last of 14 children. My wonderful parents were devout Catholics, but since Catholics suffered persecution in Vietnam, they wanted us children to escape to a different country for a better life.

The refugees usually left in tiny wooden boats, which would often capsize at sea, leaving none of the passengers alive. So, my parents decided that we would try to leave one at a time, and they made great sacrifices to save enough to pay the tremendous costs.

The first time I tried to leave, I was only nine. It took me two years and fourteen attempts before I finally managed to escape. It would take another ten years for my parents to make it across.

The Escape

Crowded onto a small wooden boat with 77 others, 11-year-old me was on my own in the middle of nowhere. We faced many hazards. On the seventh night, as a huge storm battered us, a lady beseeched me: “We may not survive this storm; whatever your religion is, pray to your God.” I responded that I had already prayed. I had, in fact, set a bargain: “Save me, and I’ll be a good boy.” As the wind and waves whipped over the boat that night, I promised to dedicate my life to serving God and His people for the rest of my life.

When I woke the next morning, we were still afloat, and the sea was calm. We were still in dire peril, however, because we had run out of food and water. Two days later, my prayers were answered when we finally landed in Malaysia after ten days at sea.

Starting a new life in a refugee camp, I set out to be faithful to the bargain I had made with God. Without parents, without anyone to take care of me, without anyone to tell me what to do, I put my total trust in God and asked Him to guide me. I went to church every day, and the priest soon asked me to be an altar server. Father Simon was a French missionary priest who worked really hard, helping refugees with all their needs, especially their immigration applications. He became my hero. He found such joy in serving others that I wanted to be like him when I grew up.

With the challenges I faced in starting a new life, I forgot my old promise. At the end of Year 10, as I thought about what I’d really like to do with my life, our Lord reminded me of my desire to become a priest. They arranged work experience for me with our parish priest, Monsignor Keating. I loved it so much that I decided to join the seminary once I completed high school. As my parents had immigrated to Australia by then, I joined Saint Charles Seminary in Perth.

Keeper of Promises

For the past 26 years, I have been serving as a priest for the Archdiocese of Perth. Like Father Simon, I have found great joy in serving God’s people. My biggest challenge was being appointed to found a new parish on the outskirts of Perth in 2015. I was at a loss. There was a school but no church or facilities, so we started by meeting to say Mass in a classroom.

I sought advice from my fellow priests. Two of their remarks stuck with me. One said: “Build a church, and then you will have people,” another said: “Build a community. When you have the people, you can build a church.” I asked myself, “Do I have the chicken, or do I have the egg?” I decided that I needed both the chicken and the egg, so I built both the community AND the church.

A Vietnamese refugee with scant chances of surviving persecution in his home country, who feared he wouldn’t live through the night of a terrifying storm in the middle of the ocean, building a church community in the Australian bush—I am still amazed at the marvelous works of the Lord!!

The Dominican Sisters helped me to build the community and also in fundraising to make Saint John Paul II Catholic Church a reality. Scores of generous hearts from other parishes in Perth and all over the world extended us a helping hand, and I am thankful to God for all their support. Instances like these repeatedly remind me that the word ‘Catholic’ means universal—no matter where we are in the world, we are the people of God. Our church, which started with a dozen people, now has over 400 parishioners. Our members come from 31 different cultures. Every week, I see new faces. As I come to learn about these diverse cultures and people who share a common faith, it helps deepen my relationship with God.

Receiving Begets Giving

Although I enjoy my life and ministry in Australia, I have not forgotten my roots in Vietnam. The Lord has been using me to support an orphanage run by Dominican Sisters. Along with fundraising, I also bring people on mission journeys to help the nuns take care of the orphans. The youth immerse themselves in the missionary work, feeding them, teaching them, doing whatever is needed, and forming a relationship that continues beyond the length of our visits. No one goes home without experiencing a profound shift in their outlook on life.

It has been over 40 years since I was on that little boat where I made a promise to God. My relationship with God had been nurtured by my parents to reach that point of surrender. When they taught me to say the Rosary, I thought it was boring. I would complain, “Why do we have to say the same prayers over and over again? Can’t we say them once and then say the same, the same, the same so I can go out and play.” But I came to appreciate that the Rosary is a summary of the entire Bible, and the repetition of prayer enables me to meditate upon the mysteries. I tell people now that BIBLE stands for Basic Information Before Leaving Earth.

My parents had given me the formation to be faithful to the promise I made on the boat, and God, in His mercy, took care of me when my parents could not. They continued to pray for their children, entrusting us to the Lord, and it was a delightful surprise for them when I became a priest. Now, it is my job to support families in nurturing faith and counseling anyone who comes to me for advice: “Do not be afraid to discern a call from God. Take time to talk to God and allow God to talk to you. You will slowly get to know what God would like you to do in your life.”

I continue to pray every day that I will truly be faithful to that promise I made to God—to be His child forevermore.

'