Encounter

Gossamer Threads

I was born in El Salvador to Protestant Missionary parents, who worked in that country planting Protestant churches for over twenty years. Growing up we understood what our parents were doing down there: they were there converting the Catholics, whose status as ‘saved’ was gravely suspect. In the view of my father in particular, only a Protestant, personal confession of faith, preferably through something akin to the “Jesus Prayer,” could guarantee that someone was actually Christian. The specifics of the prayer were left to the individual even if the content was not—the acceptance of Jesus as one’s Lord and personal Savior. That a Catholic country needed Protestant missionaries tells the basic view of Catholicism I inherited.

When I was four we moved to Canada, settling into a small duplex in Calgary with my parents, and older brother and two older sisters. My life until I was eighteen was filled with God, the Bible, and Christianity. Every day after dinner until I was eighteen, we read a chapter of the Bible, with my father quizzing us on its contents if he thought we had not paid attention. Until I was twelve, every day my mom and I would read a chapter from the Picture Bible, instilling in me both a profound love of the stories and characters of the Bible, as well as a fondness for comics. Until I was nineteen, every Sunday involved going to Church. This was not Mass-n-go, but was an hour of Sunday School where we learned about the Bible and the Christian Faith, and an hour of service consisting of a half-hour of worship, and an half-hour sermon.

The sermon was left up to the pastor to decide what to talk about, but usually involved a detailed use of the Bible in order to examine something about Christian life or culture. The summers until I was thirteen consisted of me accompanying my father to at least one, if not more, Christian camps for which he had been asked to speak. This was a regular part of my father’s life as a missionary, and my participation was seen within the context of bonding with my father and my own Christian development. Such was my formation and knowledge in the Bible and Christianity that it was not unusual in high school Sunday School or youth group for an adult to look to me when they did not know the answer to a question. But what happens when the person answering the question has questions of their own?

When I was sixteen I remember asking my Youth Minister a question. I do not remember the question, but I do remember the answer. The question was likely on the issue of evil and suffering, which was to occupy much of my undergraduate thought. I asked him a question and he gave a pat answer, one that was likely given to the youth minister as the basic answer to the question if it ever came up, one that would likely have sufficed for most others of my age.

When it came to theology and matters of God, though, I was beyond most others of my age. I showed where those pat answers failed, but also my earnest desire and hunger for a deeper answer. He grew agitated. I asked the question again. He provided a second answer, but one clearly spoken by rote rather than a serious contemplation of the matter. I probed deeper, yearning, aching for something more.

How different my world might be if that Youth Pastor had answered with a simple, “Those are good questions. I don’t know, but I’ll find out”! Instead, he angrily retorted, “You just have to have faith. If you had faith you wouldn’t ask those kind of questions!” In that moment, my Christianity died within me. My sense of God did not die, but rather my connection to Christianity.

If that was Christianity’s answer, represented by the Youth Pastor who was the duly appointed spokesperson to help me in my faith, then I knew Christianity could not be true. For I always knew that God was at least one thing: He was Truth, and if someone was afraid of questions, afraid of truth, and spoke of God as a God whose wrath was awakened by the sincere seeker, then I knew I could not follow their religion. I went to Sunday School and church, but only out of obligation and sympathy for my mother, leaving when the opportunity presented itself.

At the same time, and throughout my life, I have been given the grace of a particular awareness of the presence of God. When I was sixteen I contemplated the non-existence of God for thirty seconds, and then quickly apologized to Him for imagining the possibility of denying a presence that has been an almost always constant part of my life. I still today, even working within campus ministry and knowing well the arguments for the existence of God, sometimes have difficulty answering the atheist.

Not because their arguments are hard or challenging, but because my first instinct is always to say, “Look around you, can’t you see God everywhere?” Atheists frustrate me the same way someone who says to you, “you don’t have parents but were born in a pod and all your memories implanted” might be irritating. God’s existence is as real to me as my mother’s existence, though she died five years ago. She is gone, is not present in the flesh, but I know she existed, just as I know God exists even if I cannot see him.

Yet, when I was sixteen, that same fateful year, I asked a question to God: to show me His presence again, to feel His closeness. For that year, for reasons that only made sense almost two decades later, God’s presence was hidden from me. I could not feel His love, did not feel His presence; I knew that He was there, somewhere, but when I prayed and entreated Him there was only cold silence. I do not mean like in the famous “Footprints” poem where God carries the person, but that God was not there as I journeyed forward. He had hid Himself from me, and it felt distinctly as if He had turned His back. I did not know why. I did not care. I just wanted Him back, to feel His warm embrace again. God trusted me enough to take me on a longer journey.

If you strive here to deny that real part of my experience in the silence of God in an attempt at well-intentioned piety, what you are in danger of saying is that God does not know each of us as individuals, that He does not have a heart, love, and plan for each of us as unique persons. He does. The story of the life of each person, the story of each proto-saint, is different. It is God who takes those differences, the pain, the joy, the very heart of the person, and sees the richness of colors and threads that course through each embodied soul. From those threads, He weaves His tapestry. The silence, the distance God kept, was necessary–in hindsight–in a providence that I can only now see. What I sought was a feeling, and not God. I had wanted to pin God down, make an idol of Him, even if based on love, comfort, and long familiarity. A static love that loves the love and not the person, is not really love. As C.S. Lewis noted, He is not a tame lion. All the same, I would not wish that distance and silence on anyone, especially for one as young as I.

So at sixteen, and which only grew throughout my high school and university years, Christianity was no longer an option. Yet, at the same time, I knew God existed, even if I was not sure I was thrilled about that fact. Still, the particularities of my life also fostered my interest in the field of religious studies, where I was free to explore the truth in the big questions of life wherever the answer took me. In this way, I was open to the journey and possibility of using a variety of tools in my search for God and meaning.

A moment of Providence occurred in my fourth year of university, a moment God created to nudge me along.

I was enrolled in a class on “Modern Catholic Thought.” Less than a month before the class was to start, the professor that had been teaching it for the last thirty years had to go on emergency sick leave. There was less than twelve people registered for the class, and nobody in the department with either a background specializing in theology or Catholic thought. By all rights and reasons they should have cancelled the class, and I should not be writing this.

Instead, a long-time Instructor in Religious Studies decided to take the class on. Not having a background in theology, nor the time to develop one to satisfy an upper-level course, she took a different approach. As she put it, Catholicism is one of the only major religions that has a definitive hierarchy that publishes documents that state for the faithful official positions of the religion. Rather than study theologians, we studied the official documents of the Holy See: documents from Vatican I and II, encyclicals from various popes, statements from various departments in the Curia—these were the texts we studied.

Undoubtedly, this approach would have turned off many others from an interest in the Catholic Church. For me, though, the documents were fascinating. I was certainly not a Catholic yet, had no interest in being a Catholic, but there was a complexity and intricacy within those texts that enthralled me. I would pour over the documents, entranced by word choices that suggested a subtle exclusion of certain thoughts while emphasizing others. The care and nuance made me dig further, all the while, unbeknownst to me, one prejudice was falling. I could disagree with Catholic teaching, on contraception for instance, but I could not simply dismiss the arguments made for those positions. The people writing those documents were smart; I could disagree with them, but I could not disparage or caricature the rationality of their arguments.

I continued to pursue my quest for knowledge and understanding, continuing my studies at the Masters level. The subject of my M.A. utilized my fascination with documents from the Holy See, where I explained the use and development of the brother metaphor to describe our relations with the Jewish people. We did not always think of the Jewish people, as Saint John Paul II articulated it most fully, as our older brothers. Approaching it systematically, and wanting to be thorough, I read all of the documents published by the Holy See from 1958 until 2004. I loved it!

I was still not Catholic, the thought still had not crossed my mind, but I found myself increasingly defending Catholic teachings to my fellow graduate students. Pope Paul VI was on to something in “Humanae Vitae,” for instance, seeing a larger picture that we might have missed. It was during my M.A. that I met my first Catholic who made me think that there might be something more for me, too, in this whole ‘Catholic’ thing. His name was Angelo Guiseppe Roncalli, otherwise known as Pope John XXIII, now a saint.

Religion was always something presented to me as grave and serious, something contrary to my passionate and joyful nature, and yet here was someone who loved humor and was full of joy, seemingly with a near constant twinkle in his eye and ready wink. He became one of my dear friends, as he softened the walls further between myself and what I had constructed of God. To this day, when times are tough and my commitment to the Church and its people waver, I ask for his intercession, saying, “You got me into all this; you had better be praying for me!” And I know he does–what else would you expect from a friend.

It was not until another friend, a malcontented agnostic, challenged me that I had to confront a deeper truth. One day he asked me, out of the blue, “So, when are you going to become Catholic? We all know you are going to become Catholic, so when are you going to just do it?” In complete honesty, the reality of that possibility had not crossed my mind in any concrete way until that moment. Somebody had to ask me to make a choice, even if that someone had little interest in God. When the possibility of becoming Catholic did enter my mind in a concrete way, I was struck by something far more profound and worrisome.

Presented simplistically, in Greek philosophy the Transcendentals of Truth, Beauty, and the Good are closely linked, serving to orient ourselves to something beyond us. For some of the Church Fathers, and Aquinas after them, the Transcendentals were seen as particular ways that God calls to us. As finite creatures made in the image of an infinite God, we yearn for infinity, we yearn for something more than our own finite existence can give. That yearning for infinity finds expression in the orientation towards seeking one or more of those Transcendentals. God is Truth. God is Good. God is altogether Beautiful. As Jesus said, “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life.” He is the Way, showing us how to act within the world to others and to the world. He is the Truth, as God embodies Truth within Himself. And He is the Life, and life well-lived is beautiful, leading to the fullness of Life.

Though I had pursued Truth since at least my teens, it was also possible for me to relativize that truth into a wider cultural context. Yes, the Catholic Church has some interesting and well-thought out positions regarding life, but so do others, and I need to respect and acknowledge those other positions. Truth got me to where I was, but in the end, I could also ignore truth. But when I began to see that Truth, really see it, something changed. When I began to see the gossamer threads of those intricate documents that I loved, stretched out and linked together, all of the little threads woven into one, complete, larger image, what I glimpsed was a rich tapestry of life presented before my eyes far more beautiful than anything I had ever seen before.

Truth—that I could ignore. But beauty? Seeing it there, in all its glory, God in the center, reflected in those strands and reflecting, it demanded a response: to either take that beauty into one’s own life, or to throw a dark curtain over all of it, turning away. In doing that, though, in turning away, you know that your life will forever be diminished, will forever be less, than it could be if you were to hang that tapestry at the center of your soul, the light of the eyes fixed upon that eternal masterpiece. The beauty of the Church and her teachings beguiled me, and through it God entranced me anew, reminding me again of a dream of a more youthful love now grown fully mature.

This was all before I had ever set foot inside a Catholic Church, and well before I would attend my first Holy Mass. I had no Catholic friends, save those that I knew through books. And yet, I knew I was to become Catholic. I moved to Montreal for my Ph.D. The second thing I did after finding a place to live in the city, was to go to the McGill Newman Centre and tell someone, a man who was to become my best man, that I wanted to become Catholic.

There is one more part of the story that seems both crucial and more fitfully seen as a denouement to this story. Despite all the previous, I still went through RCIA, but there was still something more that gnawed at me. One night, a month before Easter when I was to be baptized, it came to a head. “But who do you say that I am?” Jesus asked His disciples, yet this time it was not Peter he was asking. “Well, some people say you are the Messiah, some people that you are a good person,” I replied. “But who do you say that I am?” I wrestled not with God but with myself, with my doubts and uncertainties; I struggled, fought, tears flowed, until in the deep watches of the night, I garbled out a soul-felt reply in the words of another doubter who doubted no longer when face-to-face with the reality of the risen Christ: “My Lord and my God!”

That was my answer to Christ fully alive. Now I was ready to become Catholic, to enter into a beautiful journey of a mystery that promised to take my whole life to reveal; to allow God to take the meager, fragile, gossamer threads of my own small life, to be added to His tapestry. It is a beautiful, grander tapestry far greater than anything a finite being could imagine, but a tapestry God does allow us to sometimes glimpse.

Nathan Gibbard serves as Director of Ryerson Catholic Campus Ministry in Toronto, Canada.

Related Articles

Apr 10, 2024

Evangelize

Apr 10, 2024

When a terrible loss led Josh Blakesley into the light, music from his soul became a balm to many bleeding hearts.

Growing up in the small town of Alexandria, Josh was a carefree child.

He grew up listening to his Dad’s music; two elder sisters with a great music collection was a bonus that nurtured his musical taste. Without professional training or theoretical inputs, in an age with no internet and YouTube, Josh had what he would later call ‘a side entry’ into the world of music. Starting on the drums and simultaneously learning to sing, he was enamored by the likes of Don Henley and Phil Collins, following their legendary works through magazines and books.

With his mother, though, Church was a non-negotiable matter. Thanks to her insistence, he went to Mass every Sunday. But he would leave God there and live the rest of his life on a totally different plane.

Diving Deeper

They met in Spanish class when he was 15, and unlike any other 15-year-old, she took him along to a prayer meeting. This was new and different from anything he had experienced before. Teenagers his age were coming together to worship the Lord. This worship experience was modern and engaging…with music, talks, and skits by people his age! He was intrigued, but he wouldn’t have kept coming back every week if Jenny hadn’t asked him to.

Several months later, Jenny was hit by a drunk driver and killed in an accident. Her loss was a huge blow to the entire community. As he struggled with the grief of losing her, it triggered a realization that life here is finite, and there must be purpose in it, a reason that we are living.

From that very moment, he began a journey, searching for answers to the questions that fascinated him…‘What is the reason for me? What is the purpose of what I’m doing right now? Why has God put me on this planet? What’s my role while I’m here?’

He started diving more into why we were here on this planet. In realizing that his gifts were from God, and in searching for a purpose in the use of these gifts, he realized that he wanted to give back to God and return the love.

A Bolt of Realization

He started playing music for Mass and getting involved in the liturgy. As he puts it: “There has been a faith part to my music and a music part to my faith as well. Those are still ingrained. I pray through music a lot”. And it is this experience of prayer that he tries to hand over to his brethren through writing and playing music. The “awesome and overwhelming” experience of leading people into worship and hearing them singing along makes him whisper so often: “The Lord is moving right now, and I don’t have to work.”

Bridging the Gap

Josh is now a full-time singer, songwriter, producer, music director, husband, and dad.

Even while leading the music at Mass every Sunday, Josh knows that Mass can happen without music—what a musician does at Mass doesn’t bring Jesus any greater into the room; He is there regardless. What a musician can do is “elevate the worship of the faithful by bringing some extra beauty through music.” This indeed, is one of his life goals—to try and bridge that gap and bring quality music into the liturgy.

But he doesn’t stop there; in addition to adding beauty to the Sacramental experience, he goes another mile to bring God to the people.

Right from His Heart

As a Catholic musician, Josh writes songs for the Mass and writes from the heart. Sometimes, when it comes out, it might not be out rightly Mass-material, but what comes out is still a tribute to God for the gift of music.

He relates that his song Even in This was such an experience right from his heart.

The Church community he was part of had just lost a teen, and seeing them go through the pain, the tragedy, and the devastation took him back to his own experience of losing a dear friend in his teenage years. Diving into the pain, he wrote that even in these darkest nights, God is with us. In the ‘valleys of pain’, in the ‘shattered, broken things’, in the ' hurt you cannot hide’ and the ‘fear you cannot fight’, he reassures his listeners that though you cannot see God, “You are not alone.”

This is one message Josh wants to repeat to the world: “God is moving with you.”

Mar 21, 2024

Encounter

Mar 21, 2024

Would my life ever return to normal? How can I possibly continue my work? Brooding over these, a terrible solution popped into my head…

I was finding life extremely stressful. In my fifth year at college, the onset of bipolar disorder was hindering my efforts to complete my teaching degree. I had no diagnosis yet, but I was plagued with insomnia, and I looked frazzled and unkempt, which impeded my prospects of employment as a teacher. Since I had strong natural tendencies toward perfectionism, I felt so ashamed and feared that I was letting everyone down. I spiraled into anger, despondency, and depression. People were concerned about my decline and tried to help. I was even sent to the hospital by ambulance from the school, but doctors could find nothing wrong except elevated blood pressure. I prayed but found no consolation. Even Easter Mass—my favorite time—didn’t break the vicious cycle. Why wouldn’t Jesus help me? I felt so angry with Him. Finally, I just stopped praying.

As this continued, day after day, month after month, I didn’t know what to do. Would my life ever return to normal? It seemed unlikely. As graduation approached, my fear increased. Teaching is a tough job with few breaks, and the students would need me to remain level-headed while dealing with their many needs and providing a good learning environment. How could I possibly do this in my current state? A terrible solution popped into my head: “You should just kill yourself.” Instead of casting off that thought and sending it straight back to hell where it belonged, I let it sit. It seemed like a simple, logical answer to my dilemma. I just wanted to be numb instead of under constant attack.

To my utter regret, I chose despair. But, in what I expected to be my last moments, I thought of my family and the type of person I had once been. In genuine remorse, I raised my head to the heavens and said: “I’m so sorry, Jesus. Sorry for everything. Just give me what I deserve.” I thought those would be the last words I would utter in this life. But God had other plans.

Listening to the Divine

My mother was, by providence, praying the Divine Mercy Chaplet at that very moment. Suddenly, she heard the words loud and clear in her heart “Go find Ellen.” She obediently set aside her rosary beads and found me on the floor of the garage. She caught on quickly, exclaiming in horror: “What are you doing?!” while she pulled me into the house.

My parents were heartbroken. There’s no rulebook for times such as these, but they decided to take me to Mass. I was totally broken, and I needed a Savior more than ever before. I longed for a come-to-Jesus moment, but I was convinced that I was the last person in the world He would ever want to see. I wanted to believe that Jesus is my Shepherd and would come after His lost sheep, but it was hard because nothing had changed. I was still consumed by intense self-hatred, oppressed by darkness. It was almost physically painful.

During the preparation of the gifts, I broke down in tears. I had not cried for a really long time, but once I started, I couldn’t stop. I was at the end of my own strength, with no idea where to go next. But as I wept, the weight slowly lifted, and I felt myself enfolded in His Divine Mercy. I didn’t deserve it, but He gave me the gift of Himself, and I knew that He loved me the same at my lowest point as much as He loved me at my highest point.

In Pursuit of Love

In the days to come, I could barely face God, but He kept showing up and pursuing me in the little things. I re-established communication with Jesus with the aid of a Divine Mercy picture in our living room. I tried to talk, mostly complaining about the struggle and then feeling bad about it in light of the recent rescue.

Weirdly, I thought I could hear a tender voice whispering: “Did you really think I would leave you to die? I love you. I will never forsake you. I promise to never leave you. All is forgiven. Trust in my mercy.” I wanted to believe this, but I couldn’t trust that it was true. I was growing discouraged at the walls I was erecting, but I kept chatting with Jesus: “How do I learn to trust You?”

The answer surprised me. Where do you go when you feel no hope but have to go on living? When you feel totally unlovable, too proud to accept anything yet desperately wanting to be humble? In other words, where do you want to go when you want a full reconciliation with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit but are too scared and disbelieving of a loving reception to find your way home? The answer is the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of God, and Queen of Heaven.

While I was learning to trust, my awkward attempts did not displease Jesus. He was calling me closer, closer to His Sacred Heart, through His Blessed Mother. I fell in love with Him and His faithfulness.

I could admit everything to Mary. Although I feared that I could not keep my promise to my earthly mother because, on my own, I was still barely mustering the will to live, my mother inspired me to consecrate my life to Mary, trusting that she would help me get through this. I didn’t know much about what that meant, but 33 Days to Morning Glory and Consoling the Heart of Jesus by Father Michael E. Gaitley, MIC, helped me understand. The Blessed Mother is always willing to be our intercessor, and she will never turn down a request from a child wanting to return to Jesus. As I went through the consecration, I resolved never to attempt suicide again with the words: “No matter what happens, I will not quit.”

Meanwhile, I started taking long walks on the beach while I talked with God the Father and meditated on the parable of the prodigal son. I tried to put myself in the shoes of the prodigal son, but it took me some time to get close to God the Father. First, I imagined Him at a distance, then walking toward me. Another day, I pictured Him running towards me even though it made Him look ridiculous to His friends and neighbors.

Finally, the day came when I could picture myself in the arms of the Father, then being welcomed not just to His home but to my seat at the family table. As I envisaged Him pulling out a chair for me, I was no longer a headstrong young woman but a 10-year-old girl with ridiculous glasses and a bob haircut. When I accepted the Father’s love for me, I became like a little child again, living in the present moment and trusting Him completely. I fell in love with God and His faithfulness. My Good Shepherd has saved me from the prison of fear and anger, continuing to lead me along the safe path and carrying me when I falter.

Now, I want to share my story so that everyone can know God’s goodness and love. His Sacred Heart is welling up with tender love and mercy just for you. He wants to love you lavishly, and I encourage you to welcome Him without fear. He will never abandon you or let you down. Step into His light and come home.

Mar 12, 2024

Encounter

Mar 12, 2024

Through the darkest valleys and toughest nights, Belinda heard a voice that kept calling her back.

My mother walked out on us when I was around eleven. At the time, I thought that she left because she didn't want me. But in fact, after years of silently suffering through marital abuse, she couldn’t hold on anymore. As much as she wanted to save us, my father had threatened to kill her if she took us with her. It was too much to take in at such a young age, and as I was striving hard to navigate through this difficult time, my father started a cycle of abuse that would haunt me for years to come.

Valleys and Hills

To numb the pain of my father’s abuse and compensate for the loneliness of my mother’s abandonment, I started resorting to all kinds of ‘relief’ mechanisms. And at a point when I couldn’t stand the abuse anymore, I ran away with Charles, my boyfriend from school. I reconnected with my mother during this time and lived with her and her new husband for a while.

At 17, I married Charles. His family had a history of incarceration, and he followed suit soon enough. I kept hanging out with the same bunch of people, and eventually, I, too, fell into crime. At 19, I got sentenced to prison for the first time—five years for aggravated assault.

In prison, I felt more alone than I had ever been in my life. Everyone who was supposed to love and nurture me had abandoned me, used me, and abused me. I remember giving up, even trying to end my life. For a long time, I kept on spiraling downwards until I met Sharon and Joyce. They had given their lives to the Lord. Though I had no clue about Jesus, I thought I'd give it a try as I didn't have anything else. There, trapped inside those walls, I started a new life with Christ.

Falling, Rising, Learning…

About a year and a half into my sentence, I came up for parole. Somehow in my heart, I just knew I was going to make parole because I'd been living for Jesus. I felt like I was doing all the right things, so when the denial came back with a year set off, I just didn't understand. I started questioning God and was quite angry.

It was at this time that I was transferred to another correctional facility. At the end of the church services, when the chaplain reached out for a handshake, I flinched and withdrew. He was a Spirit-filled man, and the Holy Spirit had shown him that I had been hurt. The next morning, he asked to see me. There in his office, as he asked about what had happened to me and how I was hurting, I opened up and shared for the first time in my life.

Finally, out of prison and in private rehab, I started a job and was slowly getting a hold on my new life when I met Steven. I started going out with him, and we got pregnant. I remember being excited about it. As he wanted to make it right, we got married and started a family. That marked the beginning of probably the worst 17 years of my life, marked by his physical abuse and infidelity and the continuing influence of drugs and crime.

He would even go on to hurt our kids, and this once sent me into a rage—I wanted to shoot him. At that moment, I heard these verses: “Vengeance is mine, I will repay.” (Romans 12:19) and “The Lord will fight for you” (Exodus 14:14), and that prompted me to let him go.

Never a Criminal

I was never able to be a criminal for long; God would just arrest me and try to get me back on track. In spite of His repeated efforts, I wasn't living for Him. I always kept God back, although I knew He was there. After a series of arrests and releases, I finally came home for good in 1996. I got back in touch with the Church and finally started building a true and sincere relationship with Jesus. The Church slowly became my life; I never really had that kind of a relationship with Jesus before.

I just couldn't get enough of it because I started to see that it's not the things that I've done but who I am in Christ that's going to keep me on this road. But, the real conversion happened with Bridges to Life*.

How can I Not?

Even though I hadn’t been a participant in the program as an offender, being able to facilitate in those small groups was a blessing I hadn’t anticipated—one that would change my life in beautiful ways. When I heard other women and men share their stories, something clicked inside of me. It affirmed me that I was not the only one and encouraged me to show up time and again. I would be so tired and worn out from work, but I would walk into the prisons and just be rejuvenated because I knew that that was where I was supposed to be.

Bridges to Life is about learning to forgive yourself; not only did helping others help me become whole, it also helped me heal…and I am still healing.

First, it was my mother. She had cancer, and I brought her home; I looked after her for as long as she stayed until she passed away peacefully at my home. In 2005, my father’s cancer came back, and the doctors estimated he had at most six months. I brought him home too. Everybody told me not to take in this man after what he did to me. I asked: “how can I not?” Jesus forgave me, and I feel that God would want me to do this.

Had I chosen to hold on to the bitterness or hatred toward my parents for the abandonment and the abuse, I don't know if they would have given their lives to the Lord. Just looking back over my life, I see how Jesus kept pursuing me and trying to help me. I was so resistant to feeling what was new, and it was so easy to stay in what was comfortable, but I am grateful to Jesus that I was able to finally completely surrender to Him. He is my Savior, He is my rock, and He is my friend. I just cannot imagine a life without Jesus.

Feb 10, 2024

Encounter

Feb 10, 2024

As a teenager, I did what every teen tries to do—I tried to fit in. I had this feeling, though, that I was unlike my peers. Somewhere along the way, I realized that it was my faith that made me different. I resented my parents for giving me this thing that made me stand out. I became rebellious and started to go to parties, discos, and nightclubs.

I didn't want to pray anymore. I just wanted the whole excitement of putting on makeup, dressing up, daydreaming about who's going to be at the parties, dancing all night long, and most of all, just ‘fitting in there.’

But, coming home at night, sitting on my bed all by myself, I felt empty inside. I hated who I'd become; it was a total paradox where I didn't like who I was, and yet I didn't know how to change and become myself.

On one of those nights, crying by myself, I remembered the simple happiness that I had as a child when I knew that God and my family loved me. Back then, that was all that mattered. So, for the first time in a long time, I prayed. I cried to Him and asked Him to bring me back to that happiness.

I kind of gave Him an ultimatum that if He did not reveal Himself to me in that next year, I would never return to Him. It was a very dangerous prayer but, at the same time, a very powerful one. I said the prayer and then totally forgot about it.

A few months later, I was introduced to the Holy Family Mission, a residential community where you come to learn your faith and know God. There was daily prayer, Sacramental life, frequent Confession, daily Rosary, and observation of the Holy Hour. I remember thinking, “That is way too much prayer for a single day!” At that point, I could hardly even give five minutes of my day to God.

Somehow, I ended up applying for the Mission. Every single day, I would sit in prayer in front of the Eucharistic Lord and ask Him who I was and what the purpose of my life was. Slowly but surely, the Lord revealed Himself to me through the Scriptures and from spending time in silence with Him. I gradually received healing from my inner wounds and grew in prayer and relationship with the Lord.

From the rebellious teenage girl who felt totally lost, to the joyous daughter of God, I underwent quite the transformation. Yes, God wants us to know Him. He reveals Himself to us because He faithfully answers every single prayer that we raise to Him.

Feb 08, 2024

Encounter

Feb 08, 2024

Caught in a spiral of drugs and sex work, I was losing myself, until this happened.

It was night. I was in the brothel, dressed ready for “work.” There was a gentle knock at the door, not the big bang by the police, but a truly gentle tap. The brothel lady—the Madame—opened the door, and my mother walked in.

I felt ashamed. I was dressed for this “work” that I had been doing for months now, and there in the room was my mom!

She just sat there and told me: “Sweetheart, please come home.”

She showed me love. She didn't judge me. She just asked me to come back.

I was overwhelmed by grace at that moment. I should have gone home then, but the drugs would not let me. I sincerely felt ashamed.

She wrote her phone number down on a piece of paper, slid it across, and told me: “I love you. You can call me anytime, and I'll come.”

The next morning, I told a friend of mine that I wanted to get off heroin. I was scared. At 24, I was tired of life, and it felt like I'd lived enough to be done with life. . My friend knew a doctor who treated drug addicts, and I got an appointment in three days. I called my mom, told her I was going to the doctor, and that I wanted to get off heroin.

She was crying on the phone. She jumped in the car and came straight to me. She'd been waiting…

How it all began

Our family shifted to Brisbane when my father got a job at Expo 88. I was 12. I was enrolled at an elite private girls’ school, but I just didn’t fit in. I dreamed of going to Hollywood and making movies, so I needed to attend a school that specializes in Film and TV.

I found a school renowned for Film and TV, and my parents easily gave in to my request to change schools. What I didn't tell them was that the school was also in the newspapers because they were infamous for gangs and drugs. The school gave me so many creative friends, and I excelled in school. I topped a lot of my classes and won awards for Film, TV, and Drama. I had the grades to get to University.

Two weeks before the end of grade 12, someone offered me marijuana. I said yes. At the end of school, we all went away, and again I tried other drugs...

From the kid who was laser-focused on finishing school, I went on a downward spiral. I still got into University, but in the second year, I ended up in a relationship with a guy who was a heroin addict. I remember all of my friends at the time telling me: “You're going to end up a junkie, a heroin addict.” I, on the other hand, thought I was going to be his savior.

But all the sex, drugs, and rock and roll ended up getting me pregnant. We went to the doctor, my partner still high on heroin. The doctor looked at us and immediately advised me to get a termination—she must have felt that with us, this child had no hope. Three days later, I had an abortion.

I felt guilty, ashamed, and alone. I would watch my partner take heroin, get numb, and be unaffected. I begged him for some heroin, but he was all: “I love you, I'm not giving you heroin.” One day, he needed money, and I managed to bargain some heroin in return. It was a tiny bit, and it made me sick, but it also made me feel nothing. I kept on using, the dose getting higher and higher each time.

I eventually dropped out of University and became a frequent user.

I had no idea how I was going to pay for almost a hundred dollars’ worth of heroin I was using on a daily basis. We started growing marijuana in the house; we would sell it and use the money to buy even more drugs. We sold everything we owned, got kicked out of my apartment, and then, slowly, I started stealing from my family and friends. I didn't even feel ashamed. Soon, I started stealing from work. I thought they didn’t know, but I eventually got kicked out of there too.

Finally, the only thing that I had left was my body. That first night I had sex with strangers, I wanted to scrub myself clean. But I couldn't! You can't scrub yourself clean to the inside out...But that didn’t stop me from going back. From making $300 a night and spending all of it on heroin for my partner and me, I went to make a thousand dollars a night; every cent I made went into buying more drugs.

It was in the middle of this downward spiral that my mother walked in and saved me with her love and mercy. But that wasn’t enough.

A Hole in My Soul

The doctor asked me about my drug history. As I went over the long story, my mum kept on crying—she was shocked by the fullness of my story. The doctor told me that I needed rehab. I asked: “Don't drug addicts go to rehab?” He was surprised: “You don't think you are one?”

Then, he looked me in the eye and said: “I don't think drugs are your problem. Your problem is, you have a hole in your soul that only Jesus can fill.”

I purposefully chose a rehab that I was sure to be non-Christian. I was sick, starting to slowly detox when, one day after dinner, they called us all out for a prayer meeting. I was angry, so I sat in the corner and tried to block them out—their music, their singing, and their Jesus everything. On Sunday, they took us to church. I stood outside and smoked cigarettes. I was angry, hurt, and lonely.

Begin Anew

On the sixth Sunday, August 15, it was pouring rain—a conspiracy from Heaven, in hindsight. I had no choice but to go inside the building. I stayed at the back, thinking that God couldn't see me there. I had started to become aware that some of my life choices would be considered sins, so there I sat, at the back. At the end however, the priest said: “Is there anyone in here who would like to give their heart to Jesus today?”

I remember standing in front and listening to the priest say: “Do you want to give your heart to Jesus? He can give you forgiveness for your past, a brand new life today, and hope for your future.”

By that stage, I was clean, off heroin for almost six weeks. But what I didn't realize was that there was much difference between being clean and being free. I repeated the Salvation prayer with the priest, a prayer I didn’t even understand, but there, I gave my heart to Jesus.

That day, I began a transformation journey. I got to begin anew, receive the fullness of the love, grace, and goodness of a God who had known me my whole life and saved me from myself.

The way forward was not one without mistakes. I got into a relationship in rehab, and I got pregnant again. But instead of thinking of it as a punishment for a bad choice that I had made, we decided to settle down. My partner said to me: “Let's get married and do our best to do it His way now.” Grace was born a year later, through her, I have experienced so much grace.

I've always had the passion to tell stories; God gave me a story that has helped to transform lives. He has since used me in so many ways to share my story—in words, in writing, and in giving my all to work for and with the women who are stuck in a similar life that I used to lead.

Today, I am a woman changed by grace. I was met by the love of Heaven, and now I want to live life in a way that allows me to partner with the purposes of Heaven.

Jan 06, 2024

Engage

Jan 06, 2024

It takes courage to start a 1000-piece puzzle and finish it; so is it with life.

Last Christmas, I received a 1000-piece puzzle from my Kris Kringle at work featuring the Twelve Apostles of the famous Great Ocean Road (a spectacular group of rock formations in Southwestern Victoria, Australia).

I was not keen to start. I had done three of them with my daughter a few years ago, so I knew the hard work they entail. However, as I looked at the three completed puzzles hanging at home, in spite of the inertia I was feeling, I felt an inner drive to meditate on “the Twelve Apostles.”

On Shaky Ground

I wondered how the Apostles of Jesus felt when He died on the cross and left them. Early Christian sources, including the Gospels, state that the disciples were devastated, full of disbelief and fear that they went into hiding. They were not at their best at the end of Jesus’ life.

Somehow, this is how I felt as I started the year—fearful, uneasy, sad, broken-hearted, and uncertain. I had not fully recovered from the grief of losing my dad and a close friend. I must admit my faith was standing on shaky ground. It seemed as if my passion and energy for life had been overtaken by lethargy, lukewarmness, and a dark night of the soul, which threatened to (and sometimes succeeded in) overshadowing my joy, energy, and desire to serve the Lord. I could not shake it off despite great efforts.

But if we do not stop at that disappointing episode of the disciples fleeing their Master, we see at the end of the Gospels, these same men, ready to take on the world and even to die for Christ. What changed?

The Gospels record that the disciples were transformed on witnessing the Resurrected Christ. When they went to Bethany to witness His Ascension, spent time with Him, learned from Him, and received His blessings, it had a powerful effect. He did not only give them instruction but a purpose and a promise. They were not only to be messengers but witnesses as well. He promised to accompany them in their mission and gave them a Mighty Helper at that.

This is what I have been praying for lately—an encounter with the Resurrected Jesus once more so that my life will be divinely renovated.

Not Giving Up

As I started the puzzle, trying to put together this scenic marvel of the Twelve Apostles, I recognized that every piece was significant. Every person whom I will encounter in this New Year will contribute to my growth and color my life. They will come in different hues—some strong, others subtle, some in bright pigments, others grey, some in a magical combination of tints, while others dull or fierce, but everyone necessary to complete the picture.

Jigsaw puzzles take time to put together, and so does life. There is much patience to be asked for as we connect with one another. There is gratitude for when the link is done. And when the pieces don’t fit, there is hopefully a trusting encouragement to not give up. Sometimes, we may need to take a rest from it, come back, and try again. The puzzle, like life, is not covered by splashes of bright, happy colors all the time. The blacks, the greys, and the dark shades are needed to create a contrast.

It takes courage to start a puzzle, but more so to finish it. Patience, perseverance, time, commitment, focus, sacrifice, and devotion will be demanded. It is similar to when we start to follow Jesus. Like the Apostles, will we hold on till the very end? Will we be able to meet our Lord face to face and hear Him say: “Well done, good and faithful servant” (Matthew 25:23), or as Saint Paul says: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith.” (2 Timothy 4:7)?

This year, you might be asked too: Are you holding that piece of the puzzle that could make someone’s life better? Are you the missing piece?

By: Dina Mananquil Delfino

More

Nov 22, 2023

Encounter

Nov 22, 2023

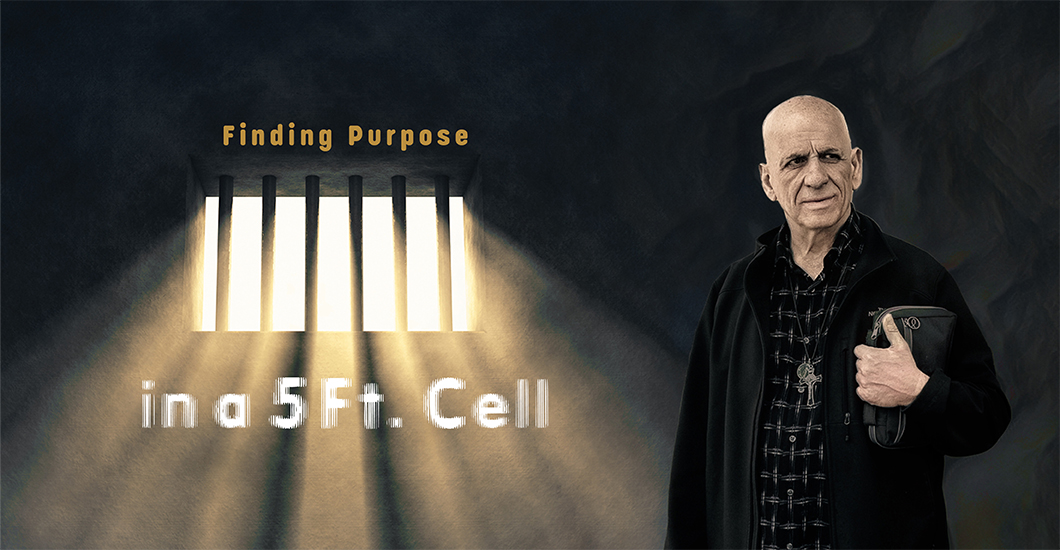

All that Tom Naemi could think of, day and night, was that he needed to get even with those who put him behind bars.

My family immigrated to America from Iraq when I was 11 years old. We started a grocery store and we all worked hard to make it successful. It was a tough environment to grow up in and I didn’t want to be seen as weak, so I never let anyone get the better of me. Though I was going to church regularly with my family and serving on the altar, my real god was money and success. So my family was happy when I married at 19; they hoped I’d settle down.

I became a successful businessman, taking over the family grocery store. I thought I was invincible and could get away with anything, especially when I survived being shot at by rivals. When another Chaldean group started another supermarket nearby, the competition became vicious. We weren’t just undercutting each other, we were committing crimes to put each other out of business. I set a fire in their store, but their insurance paid for the repair. I sent them a time bomb, they sent people to kill me. I was furious, and decided to get my revenge once and for all. I was going to kill them; my wife begged me not to but I loaded a 14-foot truck with gasoline and dynamite and drove it toward their building. When I lit the fuse, the whole truck caught fire right away. I was caught in the flames. Just before the truck exploded, I jumped out and rolled in the snow; I couldn’t see. My face, hands, and right ear melted.

I ran away down the street and got taken to the hospital. The police came to question me, but my big-shot lawyer told me not to worry. At the last minute though, everything changed, so I left for Iraq. My wife and children followed. After seven months, I quietly came back to San Diego to see my parents. But I still had grudges I wanted to settle, so trouble started again.

Crazy Visitors

The FBI raided my mom’s house. Although I escaped in the nick of time, I had to leave the country again. As business was going well in Iraq, I decided not to go back to America. Then, my lawyer called and said that if I turned myself in, he’d make a deal to get me a sentence of only 5-8 years. I came back, but I was sent to jail for 60-90 years. On appeal, the time was cut to 15-40 years, which still seemed like forever.

As I moved from prison to prison, my reputation for violence preceded me. I often got into brawls with other inmates and people were afraid of me. I still used to go to Church, but I was filled with anger and obsessed with revenge. I had an image stuck in my mind, of walking into my rival’s store, masked, shooting everyone in the store, and walking out. I couldn’t stand it that they were free while I was behind bars. My kids were growing up without me and my wife had divorced me.

At my sixth prison in ten years, I met these crazy, holy volunteers, thirteen of them, coming in every week with priests. They were excited about Jesus all the time. They spoke in tongues and talked about miracles and healing. I thought they were crazy, but I appreciated them for coming in. Deacon Ed and his wife Barbara had been doing this for thirteen years. One day, he asked me: “Tom, how is your walk with Jesus?” I told him it was great, but there was only one thing I wanted to do. As I walked away, he called me back, asking: “Are you talking about revenge?” I told him that I simply called it “getting even.” He said: “You don’t know what it means to be a good Christian, do you?” He told me that being a good Christian didn’t just mean worshiping Jesus, it meant loving the Lord and doing everything that Jesus did including forgiving your enemies. “Well”, I said, “That was Jesus; it’s easy for Him, but it’s not easy for me.”

Deacon Ed asked me to pray every day: “Lord Jesus, take this anger from me. I ask you to come between me and my enemies, I ask you to help me forgive them and to bless them.” To bless my enemies? No way! But his repeated prompting somehow got to me, and from that day, I started praying about forgiveness and healing.

Calling Back

For a long time nothing happened. Then, one day, as I was flipping through the channels, I saw this preacher on TV: “Do you know Jesus? Or are you just a Church-goer?” I felt he was talking directly to me. At 10 PM, as the power went out as usual, I sat there on my bunk and told Jesus: “Lord, all my life, I never knew you. I had everything, now I have nothing. Have my life. I give it to you. From now on, you use it for whatever you want. You will probably do a better job of it than I ever did.”

I joined Scripture study, and signed up for Life in the Spirit. During Scripture study one day, I saw a vision of Jesus in His glory, and like a laser from Heaven, I felt filled with God’s Love. The Scripture spoke to me, and I discovered my purpose. The Lord started talking to me in dreams and revealed things about people that they had never told anyone else. I started calling them from prison to talk about what the Lord had said, and promised to pray for them. Later, I’d hear about how they’d experienced healing in their lives.

On a Mission

When I was transferred to another prison, they didn’t have a Catholic service, so I started one and began preaching the Gospel there. We started with 11 members, grew to 58, and more kept joining. Men were getting healed of the wounds that had imprisoned them before they ever got into prison.

After 15 years, I returned home on a new mission—Save souls, destroy the enemy.

My friends would come home, and find me reading the Scripture for hours. They couldn’t understand what had happened to me. I told them that the old Tom had died. I was a new creation in Christ Jesus, proud to be His follower.

I lost a lot of friends but gained a lot of brothers and sisters in Christ.

I wanted to work with youth, to deliver them to Jesus so they wouldn’t end up dead or in prison. My cousins thought I had gone mad and told my mother that I would get over it soon enough. But I went on to meet the Bishop, who gave his approval, and I found a priest, Father Caleb, who was ready to work with me on this.

Before I went to prison, I had lots of money, I had popularity, and everything had to be my way. I was a perfectionist. In my old days of crime, it was all about me, but after meeting Jesus, I realized that everything in the world was garbage compared to Him. Now, it was all about Jesus, who lives in me. He drives me to do all things, and I can’t do anything without Him.

I wrote a book about my experiences to give people hope, not just people in prison, but anyone chained to their sins. We’re always going to have problems, but with His help, we can overcome every obstacle in life. It is only through Christ that we can find true freedom.

My Savior lives. He is alive and well. Blessed be the Name of the Lord!

Sep 27, 2023

Encounter

Sep 27, 2023

From being a faithful Muslim praying to Allah three times a day, fasting, almsgiving, and doing Namaz, to being baptized in the Pope’s Private Chapel, Munira’s journey has twists and turns that might surprise you!

My image of Allah was of a stern master who would punish my slightest error. If I wanted anything, I had to buy Allah’s favor with fasting and prayer. I always had this fear that if I were to do anything wrong, I would be punished.

The First Seed

A cousin of mine had a near-death experience, and he told me that he experienced a vision of plunging through a dark tunnel, at the end of which he saw a bright light and two people standing there—Jesus and Mary. I was confused; shouldn’t he have seen the prophet Mohammed or Imam Ali? Since he felt so sure that it was Jesus and Mary, we asked our imam for an explanation. He replied that Isa (Jesus) is also a great prophet, so when we die, he comes to escort our souls.

His answer didn’t satisfy me, but it began my search for the truth about Jesus.

The Search

Despite having lots of Christian friends, I didn’t know where to start. They invited me to a Novena to Our Lady of Perpetual Succour, and I started attending the novenas regularly, listening carefully to the homilies explaining the word of God. Although I didn’t understand much, I believe that it was Mary who understood and eventually led me to the truth.

In a series of dreams through which the Lord would speak to me over the years, I saw a finger pointing out a man dressed as a shepherd while a voice called me by name, saying, “Munira, follow Him.” I knew the shepherd was Jesus, so I asked who was speaking. He replied: “He and I are one.” I wanted to follow Him, but I didn’t know how.

Do You Believe in Angels?

We had a friend whose daughter seemed to be possessed. They were so desperate that they even asked me for a solution. As a Muslim, I told her that we have these Babas they could go to. Two months later, I was astounded when I saw her again. Instead of a thin, puny ghost of a figure I had seen earlier, she had become a healthy, radiant, robust teenager. They told me that a priest, Father Rufus, had delivered her in the name of Jesus.

After several refusals, when we finally accepted their invitation to join them at Mass with Father Rufus, he prayed over me and asked me to read a verse from the Bible; I felt such peace that there was no turning back. He spoke about The Man on the Cross—who died for Muslims, Hindus, and all mankind throughout the world. It awakened a deep desire to know more about Jesus, and I felt that God had sent him in answer to my prayer to know the Truth. When I came home, I opened the Bible for the first time and started reading it with interest.

Father Rufus advised me to seek out a prayer group, but I didn’t know how, so I started praying to Jesus on my own. At one point, I was alternately reading the Bible and the Quran, and I asked Him: “Lord, what is the Truth? If you are the Truth, then give me the desire to only read the Bible.” From then on, I was led to open only the Bible.

When a friend invited me to a prayer group, I initially said no, but she insisted, and the third time, I had to give in. The second time I went, I took my sister along. It turned out to be life-changing for both of us. When the preacher spoke, he said that he’d received a message, “There are two sisters here who have come searching for the Truth. Now their search has ended.”

As we attended the weekly prayer meetings, I slowly started to understand The Word, and I realized that I had to do two things—forgive and repent. My family was intrigued when they noticed a visible change in me, so they started coming too. When my dad learned about the importance of the Rosary, he surprisingly suggested that we start praying it together at home. From then on, we, a Muslim family, would kneel down and pray the Rosary every day.

No End to Wonders

My growing love for Jesus prompted me to join a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Before we went, a voice in a dream told me that although I held fear and anger deep within me, it would soon be released. When I shared this dream with my sister, wondering what it could all mean, she advised me to ask the Holy Spirit. I was puzzled because I didn’t really know who the Holy Spirit was. That would soon change in an amazing way.

When we visited the Church of Saint Peter (where he had that dream showing him all the animals that God now permitted them to eat (Acts 10:11-16)), the Church doors were closed because we were late. Father Rufus rang the bell, but nobody answered. After about 20 minutes, he said, “Let us just pray outside the Church,” but I suddenly felt a voice within me saying: “Munira, you go ring the bell.” With the permission of Father Rufus, I rang the bell. Within seconds, those huge doors opened. The priest had been sitting right beside them, but he only heard the bell when I rang it. Father Rufus exclaimed: “The Gentiles will receive the Holy Spirit.” I was the Gentile!

In Jerusalem, we visited the Upper Room where the Last Supper and the Descent of the Holy Spirit had taken place. As we were praising God, we heard a roar of thunder, a wind blew into the room, and I was blessed with the gift of tongues. I couldn’t believe it! He baptized me in the Holy Spirit in the same place where Mother Mary and the apostles received the Holy Spirit. Even our Jewish tour guide was astonished. He fell to his knees and prayed with us.

The Sprout Keeps Growing

When I returned home, I was longing to be baptized, but my mom said: “See Munira, we follow Jesus, we believe in Jesus, we love Jesus, but conversion...I don’t think we should do it. You know there will be many repercussions from our community.” But there was a deep desire within me to receive the Lord, especially after a dream in which He asked me to attend the Eucharist every day. I remember imploring the Lord like the Canaanite woman: “You fed her the crumbs from Your table, treat me like her and make it possible for me to attend the Eucharist.”

Shortly afterward, while I was walking with my dad, we unexpectedly arrived at a church where the Eucharistic celebration was just beginning. After attending the Mass, my dad said: “Let us come here every day.”

I feel that my road to baptism started there.

The Unexpected Gift

My sister and I decided to join the prayer group on a trip to Rome and Medjugorje. Sister Hazel, who was organizing it, casually asked me if I would like to get baptized in Rome. I wanted a quiet baptism, but the Lord had other plans. She spoke to the Bishop, who got us a five-minute appointment with a Cardinal that lasted two and a half hours; the Cardinal said he would take care of all arrangements to be baptized in Rome.

So we were baptized in the Pope’s Private Chapel by the Cardinal. I took on the name Fatima and my sister took on the name Maria. We joyfully celebrated our baptismal lunch with many cardinals, priests, and religious over there. I just felt that right through it all, the Lord was telling us: “O taste and see that the Lord is good; happy are those who take refuge in him” (Psalm 34:8).

Soon came the Cross of Calvary. Our family experienced a financial crisis that people in our community blamed on our conversion to Christianity. Astonishingly, the rest of my family went the other way. Instead of turning their backs on us and our faith, they also asked for baptism. Amid adversity and opposition, they found strength and courage, and hope in Jesus. Dad expressed it well, “There is no Christianity without a Cross.”

Today, we continue to encourage each other in our faith and share it with others whenever we have the opportunity. When I was speaking to my aunt about my conversion experience, she asked me why I addressed God as “Father.” God, for her, is Allah. I told her that I call Him Father because He has invited me to be His beloved child. I rejoice to have a loving relationship with Him Who loves me so much that He sent His Son to wash me clean from all my sins and reveal the promise of eternal life. After I shared my remarkable experiences, I asked her if she would still follow Allah if she were in my place.

She had no answer.

Sep 25, 2023

Evangelize

Sep 25, 2023

Blessings were abundant: friends, family, money, vacations—you name it, I had it all. So how did it all go so wrong?

I didn't really have a wonderful storybook childhood—tell me someone who has—but I wouldn't say it was terrible. There was always food on the table, clothes on my back, and a roof over my head, but we struggled. I don't just mean we struggled financially, which we definitely did, but I mean we struggled to find our way as a family. My parents were divorced by the time I was six, and my father turned to heavier drinking than ever before. Meanwhile, my mother found men who were into the same drugs and habits as she was.

Though we had a rough start, it didn't stay that way. Eventually, against all statistical odds, both of my parents and my now stepfather, by the grace of God, got sober and have stayed that way. Relationships were rebuilt, and the sun began to rise in our lives again.

A few years went by, and there came a point when I realized that I had to do something productive and different in my life so that I could avoid all of the pitfalls of my childhood. I buckled down and went back to school. I got my barber’s license and worked myself into a nice career. I made plenty of money and met the woman of my dreams. The opportunity eventually arose, and I started a second career in law enforcement in addition to cutting hair. Everyone liked me, I had friends in very high places, and it looked as if the sky was the limit.

So how'd I end up in prison?

Unbelievably True

Wait a minute, this isn't my life…this can't be real…HOW IS THIS HAPPENING TO ME?! You see, despite everything I had, I was missing something. The worst part of it was that I knew all along exactly what that something was, and I ignored it. It's not like I didn't ever try, but I just couldn't give God my everything. Instead, I lost it all…or did I?

This is how it is: Whatever sin you're holding onto will eventually work its roots deep down into the core of your soul and choke you out until you can't breathe anymore. Even seemingly insignificant sins demand more of you, little by little, until your life is upside down, and you're so disoriented that you don't know which way is up.

That's how it started for me. I began giving in to my lustful thoughts somewhere around middle school. By the time I was in college, I was a full-fledged womanizer. When I did finally meet the woman of my dreams, there was no way I could ever do what was right anymore. How could someone like me be faithful?

But that's not all.

For a while, I tried to go to Mass and do all the right things. I went to confession regularly and joined clubs and committees, but I always kept just a little bit of my old sins for myself. It's not necessarily that I wanted to, but I was so attached, and I was afraid to let go.

Time went on, and I slowly stopped going to Mass. My old sinful ways began to fester and creep back into the forefront of my life. Time moved fast, and pleasures swirled all around me as I threw caution to the wind. I was high on life. On top of it all, I was very successful and admired by many. Then it all came crashing down. I made some terrible choices that left me serving a 30-year prison sentence. More importantly, I left behind people who loved and cared for me with a lifetime of pain.

You see, sin has a way of convincing you to go further than you've gone and making you more depraved than you once were. Your moral compass becomes confused. Worse things seem more exciting, and the old sins don't cut it anymore. Before you know it, you've become someone you don't even recognize.

Fast forward to the present day...

I live in an 11x9 ft. cell, and I spend twenty-two hours a day locked inside of it. There is chaos all around me. This is not how I imagined my life would turn out.

But, I found God within these walls.

I have spent the last few years here in prison praying and seeking the help I needed. I have been studying Scripture and taking lots of classes. I've also been sharing the message of God's mercy and peace with all the other inmates who will listen to me.

It took an extreme wake-up call before I finally surrendered to God, but now that I have, my life has been totally different. I wake up every morning thankful to be alive. I am grateful every day for the shower of blessings that I receive despite my incarceration. For the first time in my life, I experienced peace in my soul. It took me losing my physical liberty to find my spiritual freedom.

You don't have to go to prison to find and accept God's peace. He will meet you wherever you are, but let me warn you—if you hold anything back from Him, you may very well end up being my neighbor in prison.

If you recognize yourself in this story, please don't wait to seek professional help and guidance, starting from, but not limited to, your local parish priest. There is no shame in admitting you have a problem, and there is no better time than NOW to get help.

If you're in prison and you're reading this, I want you to know that it's not too late for you. God loves you. He can forgive whatever it is you've done. Jesus Christ shed His precious blood to forgive all of us who come to Him with our pain and our brokenness. You can start right now, this very moment, by recognizing that you are powerless without Him. Cry out to Him with the words of the tax collector: "O God, be merciful to me, a sinner" (Luke 18:13).

I leave you with this: "What profit would there be for one to gain the whole world and forfeit his life?" (Matthew. 16:26)

Sep 20, 2023

Engage

Sep 20, 2023

Are there doors in your life that refuse to open, no matter your efforts? Know the secret behind those closed doors through this heartfelt experience.

Opening the door to the Cathedral of Saint Jude, my husband and I found our seats amidst a large crowd gathered for the funeral of a woman I had met long ago when I was only 20 years old. She and her husband were the pastoral leaders of a Catholic Charismatic Prayer Community at the time. While she and I had not been close personal friends, she had touched my life in significant ways when I was involved with this dynamic faith-filled group. Her middle son, Ken, was now Father Ken, and that day was also the 25th anniversary of his ordination to the priesthood.

Scanning the congregation revealed many familiar faces from both my past and present. Father Ken’s touching tribute to his mother and the loving eulogies by his siblings reflected the impact the prayer group had on their own family, as well as many in attendance that day. Their words prompted memories to course through my mind—of how the Holy Spirit used this community to change many lives, especially mine.

Dragged into Love

I had been raised by two very devout Catholic parents who attended Mass daily, but as a teen, I only grudgingly participated in the life of the Church. I felt resentful of my father’s insistence on family Rosary every night and saying grace not just before meals but after as well. Attending the Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament on a Friday night at 10 PM didn’t bode well for my social status as a 15-year-old, especially when my friends asked what I had done over the weekend. Being a Catholic, for me then, was just about plenty of rules, requirements, and rituals. My experience each week was not one of joy or fellowship with other believers but rather one of duty.

Still, when my sister invited me to join her at her college’s weekend retreat the fall after I graduated from high school, I agreed. My small town offered little in the way of new experiences, and this would definitely be out of the norm for me. As it turned out, this retreat would set the trajectory for the rest of my life!

Between the warm camaraderie of the participants, as well as the huge smile that covered Father Bill’s face when he shared about the Lord with us, I saw something I had never seen in my home parish, and I knew that was what I truly wanted in my life: JOY! Near the end of the weekend, during the quiet time outdoors, I offered my life to God, not knowing exactly what that really meant.

Hopeless Cases

Less than two years later, my sister and I moved from the east coast of Florida to the west, first due to her job and later, because of my acceptance to a college in Saint Petersburg. Our efforts to find a place to live within our means were thwarted time and again due to the unwillingness of numerous apartment managers to rent a one-bedroom unit to two girls—even though we had shared a bedroom our whole lives and were sisters! Discouraged after yet another refusal, we stopped at the Cathedral of Saint Jude to pray. Knowing nothing about this Saint, we spied a prayer card and discovered that Saint Jude was the ‘patron of hopeless cases.’

After a bumpy search for affordable housing, our futile situation seemed to qualify as a hopeless case, so we knelt down to invoke Saint Jude’s intercession. Lo and behold, after arriving at the next apartment complex on our list, we were again greeted with the same hesitance. However, this time, the older woman looked at me, paused, and said, “You remind me of my granddaughter. I don’t rent one-bedrooms to two women, but...I like you, and I’m going to make an exception!”

We came to find out that the nearest Catholic Church to our new home was the Holy Cross, where a group called 'Presence of God Prayer Community' met each Tuesday night. Had we been able to rent any other apartment, we would not have been led to this group of joy-filled people we soon came to call 'family!' It was clear that the Holy Spirit was at work, and His presence was revealed time and time again in the 17 years I was actively involved in the group.

Completing the Circle

Returning to Saint Jude’s, the celebration of life that day was not only of our long-ago pastoral leaders, but it was also very much my own! Remembering my brokenness as a young adult and the loneliness and insecurity I felt at that time, I marveled at how the Lord had changed my life. He used His Spirit and His people to heal me emotionally and spiritually, filling my life with deep and rich friendships that have stood the test of time. He helped me discover the gifts He had given me—the community offered me a place to serve in various ways until I realized that my natural abilities, like that of organization, could be used for spiritual purposes.

After several years, I was invited onto a new Pastoral Team whose dynamic leader mentored me by example. Through his encouragement and support, I developed leadership skills that resulted in beginning new ministries to serve the 'household of faith' in the prayer community and the 'least of these' outside the doors of the church.

When a new parish began nearby some years later, I was asked to join the music ministry there, and with the Spirit’s prompting, I also participated in various other ministries. Bringing in all that I had learned and experienced over the years, I was able to set up many events that offered opportunities for healing, conversion, and growth within our parish community. For the last 14 years, I have been blessed to organize a women’s fellowship group begun by myself and a friend, who, like me, was changed by the love and care of Christian communities.

I have found all of God’s promises in the Scriptures to be true. He is faithful, forgiving, kind, compassionate, and a source of joy deeper than any I have ever thought possible! He has provided meaning and purpose in my life, and with His grace and direction, I have been able to partner with Jesus in ministry for over 40 years now. I didn’t have to 'wander in the desert' for those years, as did the Israelites. The same God Who led His people by the “pillar of cloud by day and pillar of fire by night” (Exodus 13:22) has led me day by day, year by year, revealing His plans for me along the way.

A song from my prayer group days lilts through my mind, “Oh how good, how wonderful it is when brothers and sisters live as one!” (Psalm 133:1). Looking around that day, I saw clear evidence of that. The Spirit at work in Father Ken’s mother brought much fruit from the seeds she planted, both in her home and in our community of faith. That same Spirit then brought forth a harvest from the seeds planted and watered in my life over the years.

The Apostle Paul said it best in his letter to Ephesians:

“Now to Him who is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to His power that is at work within us, to Him be glory in the Church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations, forever and ever. Amen!” (3:20-21)