- Latest articles

My vocation story begins when I was a child of about four or five years old, growing up in Lancaster, Ohio. My Aunt Mary Ellen purchased a new reel-to-reel tape recorder and she wanted to test out the recording device. So she invited my twin sister, Joan, and I to come over a number of times and record our voices. In order to get us to start talking, she would ask us various questions: Where do you live? What is your name? What is your mother’s name? What is your daddy’s name? Then she asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Joan would always say, “I want to be a sister.” I would say, “I want to grow up and get married and have lots of children like my mother.” In my mind I knew that would be reversed, but I hesitated in saying that because I did not want to disappoint people if I did not become a sister.

When I was in second grade, I remember during my second confession the priest also asked me, “What do you want to do when you grow up?” This time, I told the truth: “When I grow up, I want to become a sister.” The priest said, “That’s a very good thought. What you need to do is pray and ask God what He is asking of you.” I took that very seriously. When I would go to Holy Mass on Sunday with my family, our missals in the pew had a prayer for vocations. I still did not want to tell anyone what I was thinking, so after communion, when my family members were bowing their heads in prayer, I would open the missal just enough to read that prayer and then close it quickly. This happened throughout my grade school years.

Then in sixth grade, during Lent, my teacher Sister Christopher showed a film strip on the passion and death of Jesus. In one scene, Jesus was shown suffering on the cross. The narrator said, “This is what your Savior has done for you. Now what will you do for your Savior?” It pierced my heart. I felt like I was the only one in the room. That was the key moment when I knew I had a desire to give myself completely to the Lord in some way. My vocation was a response to the cross. I knew then that it probably would be religious life. I did not understand it then but that was my thought.

During high school, I began to date and I got distracted, thinking perhaps I was supposed to get married. But on a retreat during my senior year, I decided to ask God—once and for all—what He wanted me to do. I remember kneeling down in my room, looking directly at a cross on the wall across from me. I heard the Lord say, “I’m calling you to be My own.” Again, my heart was pierced, and I knew then that I had to take action.

The only contact I had with religious sisters was with the Dominican Sisters of Saint Mary of the Springs in Columbus, Ohio, who taught me throughout grade school and high school. Whenever the postulants and novices would visit my school, I was always attentive and would ask questions. So, after my retreat, I told my home room teacher, Sister Sebastian, about my decision to enter religious life. She made an appointment for me to see a sister at the motherhouse in Columbus.

No one at my school knew about my vocation—yet. My father was a HAM radio operator, and he would often speak to other radio operators around the world. But sometimes his radio would interfere with our neighbor’s radio. One day during my last semester of high school, he told someone via radio that one of his twin daughters was going to enter the convent. Well, our neighbors found out and the next day at school there was a rumor that one of the Daugherty twins was going to enter the convent. Everyone knew it was me, and not Joan! Of course, I was upset with my father for spilling the beans.

I did end up visiting the motherhouse and made a decision to enter that fall, on September 8, 1959, at the age of eighteen. I made first vows July 9, 1962 and professed final vows July 9, 1967. During my first year of teaching, 1962-1963, I taught sixth grade in Steubenville, Ohio, to which I would return more than twenty years later. One of my first students was a nephew of Hollywood star Dean Martin! I taught for a total of eighteen years at elementary and Montessori schools in Ohio, New York, Pennsylvania and Michigan. I also served as principal for a total of six years at three schools in Newark, Coshocton and Columbus, Ohio.

It was in Newark that I was first exposed to the charismatic renewal, when families at a local parish there began to pray for me and invited me to go to prayer meetings with them. I eventually went to a Life in the Spirit seminar and received the Baptism of the Holy Spirit. One summer, I attended a Bible Institute at the College of Steubenville, because I knew it was charismatic. A master’s program in theology was just beginning there at the time. I had been sensing that I was going to work with young adults, so when I heard about the master’s program, my community allowed me to attend. After my first year in Steubenville, 1985-1986, a position opened on campus for a residence director for Trinity Hall. I felt that I was supposed to stay in Steubenville, so I applied for the position and got it. I would serve as the dorm director for four and a half years.

In those years on campus, I was being renewed in my own fervor in living the consecrated life. It was a call to live my religious life in a deeper way—to embrace it in a fuller way. I also was being imbued with Franciscan spirituality, although I did not realize it at first. It was awakening parts of myself that had not been awakened before. At some point, I became aware that God was calling me out of my own community. But I did not know what the next step would be. It was a frightening time in my life, not knowing what was next down the road. But I had all the assurances from the Lord that I would know when it was time.

Also during that time, the Franciscan Sisters, T.O.R. was founded. One of the original members of the community was another dorm director with whom I worked, one was a resident assistant and others were students I knew. I was very close to their founding. I watched the community grow and attract young women. I was the only woman religious on campus at the time, so whenever a young woman discerning religious life would go to the T.O.R. friars, they would send them to me. Often, they expressed a desire to join the new community. I remember thinking, “Gosh, it’s so easy for them.” My attraction to the community grew gradually.

The primary attraction was a call to a deeper contemplative prayer life. I knew that even before I felt called to join the new community, I also was drawn to their strong fraternal life, their focus on simplicity and poverty and the wearing of the habit.

I remained close to the community after it was founded—on August 15, 1988—attending Lord’s Day and dinner with them every Saturday and participating in a share group with the former dorm director, now the Reverend Mother. She and the other sisters invited me to join the community if I felt called. It had not dawned on me that it was possible for a Dominican to become a Franciscan. I spoke to my spiritual director, one of the T.O.R. friars, to help me discern what God was calling me to next. At first, he thought I was being renewed in my Dominican religious life, although I knew that was not the whole truth. There came a point when he invited me to go on a retreat he was directing for the candidates of the new community. On the retreat he asked me, “What do you think God is calling you to as the next step?” I said, “I think it’s to join the T.O.R. sisters,” and he said, “Go for it!” He helped me to take the necessary steps to request entrance into the new community. I moved in with the sisters in January 1991, entering into a time of discernment until I received the habit in July. I made final vows on March 18, 1995.

I am deeply grateful for how the Lord has worked in my life in all of its stages. He has led me down paths I never believed I would travel. My life as a Franciscan sister has been very blessed and fulfilling in so many ways. The following scripture passage is truly a reality in my life: “I will instruct you and show you the way you should walk; I will counsel you, keeping my eye on you” (Psalm 32:8).

'

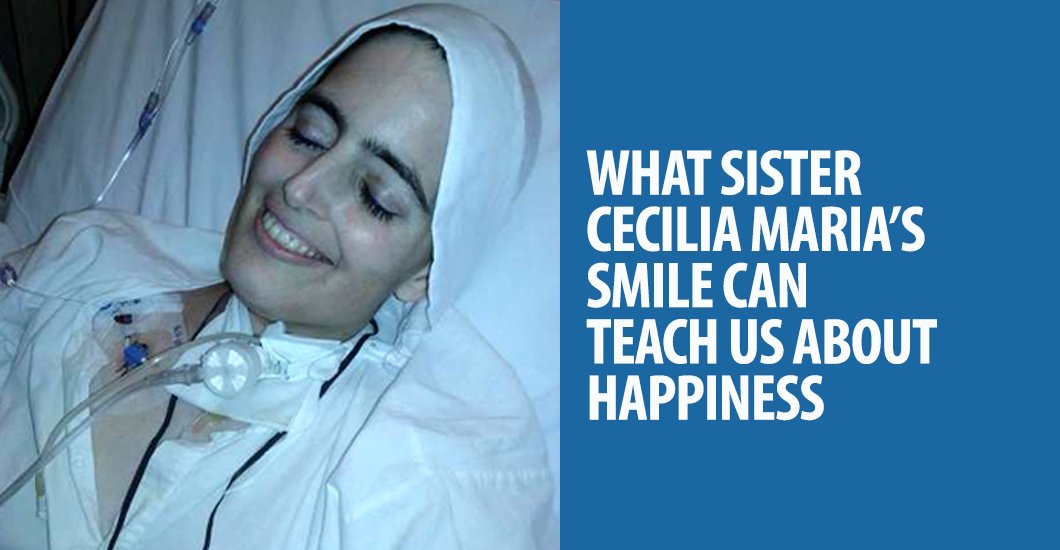

The last photo of Sister Cecilia Maria, the Argentinian Carmelite sister who recently died of cancer at age forty-three, has drawn the attention and affections of the Catholic world.

Accounts tell us that Sister often played the violin for her fellow Carmelites as a sweet gift of music, but it was in her final moment that Sister Cecilia Maria provided her smile as one last antiphon of sweetness to the world. And it is worth pondering her smile, and her life, because she had some very important lessons to teach the world.

First, she reminds us what beauty really is.

For a society that is so focused on beauty, very little attention is spent on defining beauty. What is beauty, and what relation does it have to love? What relation do love and beauty have to happiness?

These questions are not original to this author; indeed, these are the primal questions of the great literature, the great thoughts, and the great philosophy. But we have stopped asking them, not because we have answered them properly, but because we stopped caring about the questions.

Yet, regardless of philosophy, society nevertheless proffers its explanation of beauty. Sadly, these explanations are often tepid, if not altogether stupid.

Case in point. The covers of Vogue and Cosmopolitan magazines serve as a microcosm of a generation that has lost it; indeed, who is lost. The cover girls are gaunt, distant, and unhappy looking—all by editorial design. Their God-given inner beauty has been robbed; they often embody a plasticity of soullessness, and that denial of soul is a bigger lie than any airbrush could ever accomplish. These ubiquitous covers offer our wives and daughters a poorly-scripted fictional world that is governed by mannequins.

Then, in a stroke of spiritual serendipity, we see the picture of Sister Cecilia Maria; in a striking and immediate contrast to the faux world of models, we see the type of beauty that is borne of love and happiness. Among the vast array of cover girls who look dour in life, here is a woman who looks majestically happy in death.

Truly, hers is the countenance of Christianity. Christianity may not be in vogue, yet if one seeks the issue of happiness and fulfillment, the love of God is where to look.

Whereas our society is like a man who holds the key to happiness in his hand, yet insistently looks for it elsewhere, the smile of Sister Cecilia illustrates that she looked for happiness in all the right places. And found it. She showed the world the inescapable connection between love and beauty.

Second, Sister’s life and death also showed us the importance of truth, and its connection with beauty.

The worst lie ever told was that we can be happy apart from God. The original sin was the product of the original lie—a perfect untruth told by a master rhetorician. And one of those lies is that a life dedicated to God is an exercise in futility.

Ironically but predictably, much the world looks at Sister Cecilia Maria and thinks that she missed out. She missed out on almost all the things that are supposed to make women happy today. She missed out on the material of modernity. She missed out on the high-priced wardrobe, the high heels, and the high-power career, the travel, the treats, and the trinkets, the bling, the boyfriends, and the breakups. This discalced sister, spiritually tethered by her vows, whose wardrobe essentially consisted of one dress and zero shoes, missed out on everything.

Everything except happiness.

Everything except God.

In truth—because of truth—she missed out on nothing.

In truth, it is those who are insistent on sin who are missing out. As a wise priest once put it, “Sin is boring; virtue is exciting.” The biography of sin has a million chapters, but all of them are the same boring story. Each with a storyline of sadness.

Twenty-three hundred years ago, Aristotle posited that the key to happiness is simple—aggravatingly simple. Aristotle wrote that “happiness is an activity of soul in accordance with perfect virtue.” The ensuing twenty-three centuries have witnessed a world that has strenuously objected to that basic truth observed by the philosopher.

But Sister Cecilia Maria knew this central truth, and her life and death were in accordance with virtue.

One of the most exciting things about the smile of Sister Cecilia Maria is that she seemed to glimpse into a future that can be ours. For some people, that kind of thought might be intimidating. After all, the thinking might be that while Sister Cecilia Maria is exactly the kind of person who goes to Heaven, I am not.

But if that is your thinking, look a little closer at her smile. Hers is a smile of assurance and trust. It is a smile that acknowledges a merciful and loving Creator.

Whether you have lived a life like Sister Cecilia or a life like Saint Dismas, whether you have loved God since your infancy or began loving Him in your final moments, the same merciful and loving Creator awaits you.

There is a saying that Dismas “stole Heaven” in his last moments. But this is untrue. Heaven is ours—ours to gain or ours to lose. The deed to Heaven was signed in blood by Our Savior’s deed on the Cross. Heaven is not stolen; you cannot steal that which God has purchased for you. It is not Heaven, but hell that is stolen.

The beautiful truth is that God made you to be happy with Him. Sister Cecilia Maria recognized this. In her final note, she wrote, “I was thinking about how I would like my funeral to be. First, some intense prayer, and then a great celebration for everyone. Don’t forget to pray, but don’t forget to celebrate either!”

Sister Cecilia Maria’s death, her life, and her smile were a testimony to happiness. Our Lord assured us that the world would know we are Christians by our love. What Sister reminded us is that part of that love is a smile.

'

I guess you never know how little faith you have until it is tested. Faith never grows, unless it is tested. I have found it to be a vicious lifelong cycle. I think I have faith, it gets tested, and I realize how little faith I have after all.

I have been praying for something for what seems to be a long time. A “long time” in human terms is anywhere from fifteen minutes to decades. In actuality, when I have the benefit of hindsight, I can see where God may have been working in the background lining everything up, but I did not notice because I was too preoccupied thinking He was not listening or doing anything. “Doing anything” meaning, what I wanted, how I wanted it, and when I wanted it done.

I am pathetically impatient.

Currently, I am seeing the fruit of what I consider to be about twelve years of praying coming to fruition in a series of unexpected rapid-fire events. Okay, truth be told, it was really eight years of whining and four years of determined praying, but you get it. Unpredicted circumstances have netted us a new pastor, new possibilities, and a renewed sense of hopefulness. Issues that had been stomped down, or placed in a permanent holding pattern are quickly seeing life. New energy and a real sense of leadership have taken a hold of the community. It is refreshing and at the same time, nothing we could have imagined. God’s ways often take us by surprise!

Things can turn on a dime; we all know that. It seems like we wait ages for something to happen and then, boom it happens out of nowhere. I was reminded of that when a year ago an encounter with a car almost ended my life. Each day when I drive to work I glance at the very spot where I laid on the pavement unconscious. I thank God, in His mercy, for giving me another chance to learn important life lessons, like patience, which I apparently will need three additional lifetimes to advance past even the most rudimentary lessons. I am impatient even when learning patience.

I want to see things change now. I think I know the best case scenario and of course, share my perspective of this with the Lord. I know He has a sense of humor because He does not entertain any of my ideas. “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways…” Just last week He reminded me of that passage from Isaiah 55:8. I did not think that He was listening. Apparently He was.

What I am beginning to realize is that life is like a playground. It is the place where we can play out possibilities, make mistakes, skin our knees, and get put in time out as we work out life. God can make lessons out of mistakes, heal the wounds of bad choices and open doors that were previously shut. Pope Francis likes to say, let God surprise you.

I like surprises. I just hate waiting for them.

As I pray the Rosary or read the Gospels it has occurred to me how much joy and sorrow are intermingled. Life, in reality, is bittersweet. There are times to wait, to celebrate, and to mourn. For example, teenage Mary is pregnant with the Son of God! Scary but great news. The Son is born and with it, the limitless joy of holding your newborn. Then the news about a sword of sorrow piercing her heart. While you are at it, pack with haste and head to Egypt for the child’s life is in mortal danger. All this just in the first couple of years, and did not get better for long from there. Over and over there is good news and great joy, coupled with immense sorrow, and pain.

God does not ask us to endure anything that He did not ask of His beloved Son and His family. There is a lesson in this for us all and reminds me of one of my favorite prayers by Saint Teresa of Avila:

Let nothing disturb you,

Let nothing frighten you,

All things are passing away:

God never changes.

Patience obtains all things

Whoever has God lacks nothing;

God alone suffices.

“Patience obtains all things.” Thank you Lord for loving me enough and giving me the time to learn the hardest lessons which grow my tiny molecule-sized faith. Teach me patience and trust in You.

'

The invitation to say the “Our Father” is one of the most beautiful, glossed-over treasures in the Holy Mass: “At the Savior’s command and formed by divine teaching, we dare to say.”

Unworthy as we are to utter such intimacy—and when Christ first taught us to do it, what a foolhardy notion it must have seemed—we call Him Father; we call Him ours.

What could be more daring?

Perhaps to say, “I have no heavenly father.”

These were the words I heard from my youngest brother in an e-mail titled, “I don’t believe in God.” It hit me like a punch to the gut.

There is nothing noteworthy about one more dejected, misanthropic millennial. But it is noteworthy when he is my brother, because I have seen God’s paternal hand leading him through life, endowing him with grace. My brother was called for a special purpose, even from his youngest years.

At three years old on Christmas Eve, his furrowed brow peered over construction paper while his pudgy fist scribbled furiously with a magic marker. While the rest of us had sugarplums and Legos dancing in our heads, he had the Birth in mind. And it was with gentle conviction that the youngest of us would demand to go to the nativity set at church to lay a newspaper-wrapped birthday card for baby Jesus, lying in the manger.

Two years later, my family was rifling through possessions my mom was prodding us to collect for the homeless; I was pettily hoarding my clothes that no longer fit, while Keegan, with the authentic purity that could only come from someone who had just learned of homelessness, pulled his baby blanket off his bed, and sent it to those who clearly needed it more.

And later that year when we entered my mom’s hospital room, as she lay sutured after a mastectomy, it would once more be tiny Keegan, moved by a holy haste and a divine knowledge, who would find a small scrap of skin untouched by tubes and tape and gently pat her while tears rolled down her cheeks.

The stories are many and precious to me: him rolling out of bed on summer mornings for daily Mass, his desire to be a priest, his visits to the adoration chapel, his beautiful voice singing “Ave Maria” at my wedding. They gnaw at me like a painful reminder of how God sees him.

When graduating from high school, I impishly asked him what the most important piece of advice he could give me was, and without a beat he said, “Ask without reserve.”

How those words haunt me now; like an echo from the past they reverberate over the moments when De Sales and Aquinas were replaced with Nietzsche and Hume. The trips to the chapel replaced by coffee with fellow skeptics. The sweet drawing of Jesus the Shepherd in his bedroom stared at through increasingly ironic eyes. The fidgeting hands during family prayers and rosaries. The discomfort. The smirks. The silence.

It is difficult to reconcile the memories of my baby brother with the man in front of me saying, “I don’t believe in God”; difficult to hear him come to such a conclusion when his whole existence has been a stark contrast to godlessness.

But my memories are God’s whispers to me of the way He sees my brother still, His beloved son.

When we were given a filial relationship with our Creator, it was not by our merit. It was Christ interceding, “Here am I and the children You gave me.” It is Christ who died on our behalf, who gave us the gratuitous incarnation and intimacy with the Father. We do not earn His fatherhood; He just is our Father.

So while my brother is telling me he no longer believes in God, God’s hands are on both our shoulders as the news is shared.

While he strengthens his self-mastery through yoga, every breath in and out will still be the ruah that God breathed into him on his first day. And while he reads Nietzsche and every other philosopher on the planet, God will be still watching over him in his earnest pursuit. And God-willing, someday when he has stumbled on Augustine, and he is out in his garden and has his falling-over conversion, God will lift his head up, look him in the eyes and say, “You are my son, you have always been my son. Come home.”

And we will say “Our Father” once again.

'

I was born in El Salvador to Protestant Missionary parents, who worked in that country planting Protestant churches for over twenty years. Growing up we understood what our parents were doing down there: they were there converting the Catholics, whose status as ‘saved’ was gravely suspect. In the view of my father in particular, only a Protestant, personal confession of faith, preferably through something akin to the “Jesus Prayer,” could guarantee that someone was actually Christian. The specifics of the prayer were left to the individual even if the content was not—the acceptance of Jesus as one’s Lord and personal Savior. That a Catholic country needed Protestant missionaries tells the basic view of Catholicism I inherited.

When I was four we moved to Canada, settling into a small duplex in Calgary with my parents, and older brother and two older sisters. My life until I was eighteen was filled with God, the Bible, and Christianity. Every day after dinner until I was eighteen, we read a chapter of the Bible, with my father quizzing us on its contents if he thought we had not paid attention. Until I was twelve, every day my mom and I would read a chapter from the Picture Bible, instilling in me both a profound love of the stories and characters of the Bible, as well as a fondness for comics. Until I was nineteen, every Sunday involved going to Church. This was not Mass-n-go, but was an hour of Sunday School where we learned about the Bible and the Christian Faith, and an hour of service consisting of a half-hour of worship, and an half-hour sermon.

The sermon was left up to the pastor to decide what to talk about, but usually involved a detailed use of the Bible in order to examine something about Christian life or culture. The summers until I was thirteen consisted of me accompanying my father to at least one, if not more, Christian camps for which he had been asked to speak. This was a regular part of my father’s life as a missionary, and my participation was seen within the context of bonding with my father and my own Christian development. Such was my formation and knowledge in the Bible and Christianity that it was not unusual in high school Sunday School or youth group for an adult to look to me when they did not know the answer to a question. But what happens when the person answering the question has questions of their own?

When I was sixteen I remember asking my Youth Minister a question. I do not remember the question, but I do remember the answer. The question was likely on the issue of evil and suffering, which was to occupy much of my undergraduate thought. I asked him a question and he gave a pat answer, one that was likely given to the youth minister as the basic answer to the question if it ever came up, one that would likely have sufficed for most others of my age.

When it came to theology and matters of God, though, I was beyond most others of my age. I showed where those pat answers failed, but also my earnest desire and hunger for a deeper answer. He grew agitated. I asked the question again. He provided a second answer, but one clearly spoken by rote rather than a serious contemplation of the matter. I probed deeper, yearning, aching for something more.

How different my world might be if that Youth Pastor had answered with a simple, “Those are good questions. I don’t know, but I’ll find out”! Instead, he angrily retorted, “You just have to have faith. If you had faith you wouldn’t ask those kind of questions!” In that moment, my Christianity died within me. My sense of God did not die, but rather my connection to Christianity.

If that was Christianity’s answer, represented by the Youth Pastor who was the duly appointed spokesperson to help me in my faith, then I knew Christianity could not be true. For I always knew that God was at least one thing: He was Truth, and if someone was afraid of questions, afraid of truth, and spoke of God as a God whose wrath was awakened by the sincere seeker, then I knew I could not follow their religion. I went to Sunday School and church, but only out of obligation and sympathy for my mother, leaving when the opportunity presented itself.

At the same time, and throughout my life, I have been given the grace of a particular awareness of the presence of God. When I was sixteen I contemplated the non-existence of God for thirty seconds, and then quickly apologized to Him for imagining the possibility of denying a presence that has been an almost always constant part of my life. I still today, even working within campus ministry and knowing well the arguments for the existence of God, sometimes have difficulty answering the atheist.

Not because their arguments are hard or challenging, but because my first instinct is always to say, “Look around you, can’t you see God everywhere?” Atheists frustrate me the same way someone who says to you, “you don’t have parents but were born in a pod and all your memories implanted” might be irritating. God’s existence is as real to me as my mother’s existence, though she died five years ago. She is gone, is not present in the flesh, but I know she existed, just as I know God exists even if I cannot see him.

Yet, when I was sixteen, that same fateful year, I asked a question to God: to show me His presence again, to feel His closeness. For that year, for reasons that only made sense almost two decades later, God’s presence was hidden from me. I could not feel His love, did not feel His presence; I knew that He was there, somewhere, but when I prayed and entreated Him there was only cold silence. I do not mean like in the famous “Footprints” poem where God carries the person, but that God was not there as I journeyed forward. He had hid Himself from me, and it felt distinctly as if He had turned His back. I did not know why. I did not care. I just wanted Him back, to feel His warm embrace again. God trusted me enough to take me on a longer journey.

If you strive here to deny that real part of my experience in the silence of God in an attempt at well-intentioned piety, what you are in danger of saying is that God does not know each of us as individuals, that He does not have a heart, love, and plan for each of us as unique persons. He does. The story of the life of each person, the story of each proto-saint, is different. It is God who takes those differences, the pain, the joy, the very heart of the person, and sees the richness of colors and threads that course through each embodied soul. From those threads, He weaves His tapestry. The silence, the distance God kept, was necessary–in hindsight–in a providence that I can only now see. What I sought was a feeling, and not God. I had wanted to pin God down, make an idol of Him, even if based on love, comfort, and long familiarity. A static love that loves the love and not the person, is not really love. As C.S. Lewis noted, He is not a tame lion. All the same, I would not wish that distance and silence on anyone, especially for one as young as I.

So at sixteen, and which only grew throughout my high school and university years, Christianity was no longer an option. Yet, at the same time, I knew God existed, even if I was not sure I was thrilled about that fact. Still, the particularities of my life also fostered my interest in the field of religious studies, where I was free to explore the truth in the big questions of life wherever the answer took me. In this way, I was open to the journey and possibility of using a variety of tools in my search for God and meaning.

A moment of Providence occurred in my fourth year of university, a moment God created to nudge me along.

I was enrolled in a class on “Modern Catholic Thought.” Less than a month before the class was to start, the professor that had been teaching it for the last thirty years had to go on emergency sick leave. There was less than twelve people registered for the class, and nobody in the department with either a background specializing in theology or Catholic thought. By all rights and reasons they should have cancelled the class, and I should not be writing this.

Instead, a long-time Instructor in Religious Studies decided to take the class on. Not having a background in theology, nor the time to develop one to satisfy an upper-level course, she took a different approach. As she put it, Catholicism is one of the only major religions that has a definitive hierarchy that publishes documents that state for the faithful official positions of the religion. Rather than study theologians, we studied the official documents of the Holy See: documents from Vatican I and II, encyclicals from various popes, statements from various departments in the Curia—these were the texts we studied.

Undoubtedly, this approach would have turned off many others from an interest in the Catholic Church. For me, though, the documents were fascinating. I was certainly not a Catholic yet, had no interest in being a Catholic, but there was a complexity and intricacy within those texts that enthralled me. I would pour over the documents, entranced by word choices that suggested a subtle exclusion of certain thoughts while emphasizing others. The care and nuance made me dig further, all the while, unbeknownst to me, one prejudice was falling. I could disagree with Catholic teaching, on contraception for instance, but I could not simply dismiss the arguments made for those positions. The people writing those documents were smart; I could disagree with them, but I could not disparage or caricature the rationality of their arguments.

I continued to pursue my quest for knowledge and understanding, continuing my studies at the Masters level. The subject of my M.A. utilized my fascination with documents from the Holy See, where I explained the use and development of the brother metaphor to describe our relations with the Jewish people. We did not always think of the Jewish people, as Saint John Paul II articulated it most fully, as our older brothers. Approaching it systematically, and wanting to be thorough, I read all of the documents published by the Holy See from 1958 until 2004. I loved it!

I was still not Catholic, the thought still had not crossed my mind, but I found myself increasingly defending Catholic teachings to my fellow graduate students. Pope Paul VI was on to something in “Humanae Vitae,” for instance, seeing a larger picture that we might have missed. It was during my M.A. that I met my first Catholic who made me think that there might be something more for me, too, in this whole ‘Catholic’ thing. His name was Angelo Guiseppe Roncalli, otherwise known as Pope John XXIII, now a saint.

Religion was always something presented to me as grave and serious, something contrary to my passionate and joyful nature, and yet here was someone who loved humor and was full of joy, seemingly with a near constant twinkle in his eye and ready wink. He became one of my dear friends, as he softened the walls further between myself and what I had constructed of God. To this day, when times are tough and my commitment to the Church and its people waver, I ask for his intercession, saying, “You got me into all this; you had better be praying for me!” And I know he does–what else would you expect from a friend.

It was not until another friend, a malcontented agnostic, challenged me that I had to confront a deeper truth. One day he asked me, out of the blue, “So, when are you going to become Catholic? We all know you are going to become Catholic, so when are you going to just do it?” In complete honesty, the reality of that possibility had not crossed my mind in any concrete way until that moment. Somebody had to ask me to make a choice, even if that someone had little interest in God. When the possibility of becoming Catholic did enter my mind in a concrete way, I was struck by something far more profound and worrisome.

Presented simplistically, in Greek philosophy the Transcendentals of Truth, Beauty, and the Good are closely linked, serving to orient ourselves to something beyond us. For some of the Church Fathers, and Aquinas after them, the Transcendentals were seen as particular ways that God calls to us. As finite creatures made in the image of an infinite God, we yearn for infinity, we yearn for something more than our own finite existence can give. That yearning for infinity finds expression in the orientation towards seeking one or more of those Transcendentals. God is Truth. God is Good. God is altogether Beautiful. As Jesus said, “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life.” He is the Way, showing us how to act within the world to others and to the world. He is the Truth, as God embodies Truth within Himself. And He is the Life, and life well-lived is beautiful, leading to the fullness of Life.

Though I had pursued Truth since at least my teens, it was also possible for me to relativize that truth into a wider cultural context. Yes, the Catholic Church has some interesting and well-thought out positions regarding life, but so do others, and I need to respect and acknowledge those other positions. Truth got me to where I was, but in the end, I could also ignore truth. But when I began to see that Truth, really see it, something changed. When I began to see the gossamer threads of those intricate documents that I loved, stretched out and linked together, all of the little threads woven into one, complete, larger image, what I glimpsed was a rich tapestry of life presented before my eyes far more beautiful than anything I had ever seen before.

Truth—that I could ignore. But beauty? Seeing it there, in all its glory, God in the center, reflected in those strands and reflecting, it demanded a response: to either take that beauty into one’s own life, or to throw a dark curtain over all of it, turning away. In doing that, though, in turning away, you know that your life will forever be diminished, will forever be less, than it could be if you were to hang that tapestry at the center of your soul, the light of the eyes fixed upon that eternal masterpiece. The beauty of the Church and her teachings beguiled me, and through it God entranced me anew, reminding me again of a dream of a more youthful love now grown fully mature.

This was all before I had ever set foot inside a Catholic Church, and well before I would attend my first Holy Mass. I had no Catholic friends, save those that I knew through books. And yet, I knew I was to become Catholic. I moved to Montreal for my Ph.D. The second thing I did after finding a place to live in the city, was to go to the McGill Newman Centre and tell someone, a man who was to become my best man, that I wanted to become Catholic.

There is one more part of the story that seems both crucial and more fitfully seen as a denouement to this story. Despite all the previous, I still went through RCIA, but there was still something more that gnawed at me. One night, a month before Easter when I was to be baptized, it came to a head. “But who do you say that I am?” Jesus asked His disciples, yet this time it was not Peter he was asking. “Well, some people say you are the Messiah, some people that you are a good person,” I replied. “But who do you say that I am?” I wrestled not with God but with myself, with my doubts and uncertainties; I struggled, fought, tears flowed, until in the deep watches of the night, I garbled out a soul-felt reply in the words of another doubter who doubted no longer when face-to-face with the reality of the risen Christ: “My Lord and my God!”

That was my answer to Christ fully alive. Now I was ready to become Catholic, to enter into a beautiful journey of a mystery that promised to take my whole life to reveal; to allow God to take the meager, fragile, gossamer threads of my own small life, to be added to His tapestry. It is a beautiful, grander tapestry far greater than anything a finite being could imagine, but a tapestry God does allow us to sometimes glimpse.

'

In high school, I had a friend in my youth group who had a tendency to live a pretty reckless life. She liked going out and partying. She liked spending time with boys, hooking up and never seeing them again. She would go out and party on Saturday night but come to youth group and church on Sunday. She always had wonderful spiritual insight, but she thought it was too late for her because she was carrying so much sin. She was a nice girl who was very charming, but had an addiction.

By the grace of God, she went to a summer conference with the youth group going into our sophomore year. The conference had a women’s session where a young woman talked about the values and beauty of chastity and purity and the fulfillment that comes with it. My friend left ready to turn over a new leaf. There was a booth that was selling purity rings. I have worn one for years and encouraged her to buy one, which she did.

We got back to school and about a month later she was still wearing the ring and had not gone out to an immoral high school party. But on our second or third day of school, she was eating lunch with a guy who was a friend of hers and he asked her about the ring. She told him about the conference and the ring.

He mocked her, “Isn’t it a bit late for you to wear that?”

Humiliated, she took off the ring and never wore it again. Within a few months, she had fallen back to her old ways. The lesson to pull from this story is a lesson that my friend did not learn. It is never too late to turn over a new leaf.

Forgive Yourself

This does not mean you forget, but do not let it come back and haunt you, effecting your happiness. It is so easy to fall into a depression when you look back on your mistakes. Stop kicking yourself when you do not need to.

The result of those mistakes is that you grow stronger and are better able to recognize the emptiness that the hookup culture brings and the joy that comes with being chaste. That is a gift that comes from the ashes of your previous life.

Make A Promise To Yourself

Make it tangible and keep it as a reminder. This can be done by using a ring or another piece of jewelry. Write a contract or a statement and put it somewhere you will see it every day. Give yourself a visual reminder of that promise.

I wear a purity ring, which may seem out of style, especially for someone my age, but I love it. It is a tangible reminder for me to remain pure and chaste, and it also gives me many opportunities to witness to others a chaste life and the joy that it brings me.

One of my friends bought a case for her phone with the words from Matthew 5:8, “Blessed are the pure of heart, for they will see the kingdom of God.” That serves as her reminder because she looks at it multiple times a day.

Another idea is to find a quote from a chastity speaker or a verse from the Bible and save it as your wallpaper for your phone or computer. Hang a reminder on the ceiling above your bed so that it is the first thing you see when you wake up and the last thing before you fall asleep.

People are going to speak up. Do not let them get to you.

Living a pure, chaste life is not easy. It is not mainstream. Hookups and sex outside of marriage promise immediate satisfaction, but it is very temporary and will ultimately leave you empty and alone.

People will think it is odd. Those who speak up about it will be the people who are close to you; your friends, your family.

I heard a chastity speaker say that if you are struggling with temptations and want to fall back, you are doing chastity right. Keep going and hold onto that promise. It will not leave you broken, it will ultimately fulfill you.

Do not coward away. Be a witness to the fulfillment of chastity. Answer their questions and if they are out of line in their comments to you, tell them. It could inspire them to observe their own brokenness. Begin a chain reaction in your friend group.

And always remember, if you do fall back and make a mistake, it is never too late to start over again.

'

There is no question I receive more from people online or at events than “Hey Mark, what’s your favorite Bible verse?” Of course, questions about whether or not Matt Maher has more gray hair than I do come in as a close second … but I digress. There is possibly no question easier, yet more difficult, to answer.

Choosing one “favorite” Bible verse, for me, is like trying to choose a favorite child. It is impossible (although, my favor often rests on the child who is not sugared up and acting like a demoniac).

You see, different “seasons” of life bring with them different needs and struggles, joys and failures. In this way and for this reason, every season has a different verse that I tend to lean on or look to for support, direction or just plain hope.

I have several favorite verses, to be honest.

◗ After a long and tiring day of ministry, I find solace in Nehemiah 8:10

◗ When the Lord feels distant, or falls silent, I lean into James 4:8

◗ In those times my family or I am suffering, I rush to Revelation 21:4

◗ In times when I am overwhelmed with gratitude and God’s goodness, I turn to Psalm 95:2 and 1 Thessalonians 3:9

◗ In times of confusion, I lean on Proverbs 3:5-6

◗ When the future looks bleak, I pray Romans 8:28 and Jeremiah 29:11-12 until I actually trust in those words Again.

Beyond all of these great nuggets of timeless wisdom, however, there is one verse that encapsulates each of these sentiments and more. It comes from the Prophet Isaiah, given to him at a time of great darkness, when he (and his nation) were falling into hopelessness:

“Fear not, for I am with you, be not dismayed, for I am your God; I will strengthen you, I will help you, I will uphold you with my victorious right hand.” —Isaiah 41:10

I love this verse on so many levels. It is clear and concise. It is present and unwavering. It is strong but still tender, challenging yet comforting. In short, it is everything a good Father should be.

There is no command more repeated in Scripture than “fear not.” The repetition of that command is not because God is forgetful, but because we are. God knows we are often tempted to give in to fear. However, pay attention to the “why.” God tells us not to fear, because He is with us.

Think about the first time you were left alone as a child or lost sight of your parent in a crowded store. Fear comes like a tidal wave. Yet, that moment your eyes lock onto your parent again ushers in a reclaimed peace and security. How often in your life are you filled with fear? If we are present enough to the situation and aware enough to pray—and call God into the situation—that fear quickly turns to dust.

Pay close attention to what the Spirit breathes in this verse. For not only does God bid us not to fear and remind us of His eternal (dare I even say “Eucharistic”) presence with us, but He tells us there is no reason to dismay for He is God.

God is God; I am not. No matter how hard we try or how often we act like it, that simple truth brings freedom and peace. There is a God who cares for me and about me and is with me and desires a relationship with me. What we call a storm, He calls a path. Moses didn’t part the sea nor Peter tread upon it because they willed it, but because God did.

This second part of my favorite verse invites me (and you) to trust in His power over my own. God shifts the gears slightly, making three promises to us:

- The Father will strengthen you.

- The Father will help you.

- The Father will uphold you.

You would be wise to commit these promises and, actually, the entire verse to memory. Write them down in your own handwriting. Plaster them on your mirrors, your walls, your dashboard, tattoo them on the insides of your eyelids if it will help you.

God is not going anywhere. He will fight the battle for you (Exodus 14:14). He will be our help, our rock, our fortress, and our deliverer (Psalm 18:2). He will also be there when we fall or jump into the pit and He will lift us out (Psalm 40:2). Like a good father, He will take us by the hand and lead us to victory, as the verse promises in its conclusion.

People are often surprised when I share this “favorite verse” with them. It is as though they think I never doubt or struggle, as if the person holding the microphone or writing the book must “have it all figured out.”

To be clear, the only thing I have figured out is that I have nothing figured out, except this: I need Jesus. I need Jesus more and more every day. I cannot imagine my life without Him nor would I want to do so.

Acknowledging your need for God does not make you weak; it makes you self-aware and honest. Admitting that you do not have it all together does more than make you merely human; it makes you humble. The more you learn to look to and lean on God’s promises, the easier it becomes to trust in them and, ultimately, in Him.

I do not share these verses, write, speak, or tweet because I have nothing better to do, but because I have no One better to share. I do not have all the answers but I know the answer and His name is Jesus Christ. I would like to end with a challenge: I have cited about a dozen verses. More often than not, when we read we do not actually take the time to look up verse

citations. I would like to ask you to do it this time. Grab your own Bible and highlighter. Open to each and let God’s truth pierce your heart and penetrate your soul in a new way.

Ultimately, it does not matter what my favorite verse is—it is about whether or not I let the Word of God dwell in me richly (Colossians 3:16) and whether you do. Life is not a wrestling match of “God versus you” but, rather, a love story where God verses you—all you have to do is turn His holy page each day and let Him.

Happy reading.

'

We do not use hashtags in our daily experience of religious life (unlike many of you, dear readers), but if we did, a lot of our posts these days would probably say #TRANSITION.

It is just that time of year. In early August, our sisters move to their respective mission houses, our novices make first vows, our postulants become novices and new postulants come our way. Some sisters have the same assignments they had last year, and others have new—sometimes dramatically new—assignments. We call it #transition.

Another hashtag would be #thegraceforthat. I joked with a sister a few days ago—there is a grace for that! Wherever the Lord puts us, He gives us the grace to be there—to do that specific thing, to be His light in that specific way. But sometimes it is hard to see for all the newness. Where is it to be found? Where is the grace? I am in the midst of #transition as well. Sure, I am still here at the motherhouse and still working in the heart of the home (aka, the kitchen), but now I have the responsibility of coordinating all of it.

It can be easy to compare. “Last year, I didn’t have to …” “Her assignment is so much more exciting …” It can be easy to be discontent.

I realized something recently—I do not have the grace to do anything else right now. I do not have the grace to serve the poor or to minister to college students, as our mission house sisters do. I do not have the grace to teach the novices. I definitely do not have the grace to be the Reverend Mother! I am exactly where He wants me, where the grace is. If I look more closely, I can see it. I can see how He has gifted me and put me right where I can use my gifts for the greater good.

Saint Peter writes, “As generous distributors of God’s manifold grace, put your gifts at the service of one another, each in the measure he has received” (1 Peter 4:10). The stay-at-home mom who offered to bake and decorate the cakes for our celebrations this summer has the grace, the gift, for that. The retired painter who volunteered his time for a couple of weeks to help repaint our dining room and hallways has #thegraceforthat. The married couple with children who farm and garden here at our motherhouse property and share the bounty with us have #thegraceforthat. They all put their graces, ultimately God’s gifts, at the service of others. I can do the same! Why would I want to do anything without His help?

Just because God supplies it does not mean it is easy to share the grace. But it is comforting to know He is ultimately the source. I am just distributing what He gives. Where is the grace? It is right here. I am already knee-deep in it. I just have to move my feet forward to feel the rush, the wetness, around me. I have to move. When I am standing still, looking back at where I was, I cannot see the grace I have for today or for tomorrow.

So, in the midst of all the #transitions, I know God is the same, and His hands are always open, full of gifts. I want to stay right here, where the grace is.

'

I carry wounds. I carry scars. I carry pains. I carry all of these pieces of sadness, loneliness, challenge, and despair inside me. Some wounds are visible and others are buried deep inside my heart. I have been a part of causing wounds and others have inflicted me with wounds. I have healed from and I have ignored my wounds. I carry wounds but I also am learning how to ask for help in binding them.

I recently attended a retreat that focused on grace and the “wounded healer.” Throughout the time I had the opportunity to reflect on where I am on this life journey and what has happened, is happening, or will happen in the future. Immediately, I thought of Henri Nouwen’s book, “Wounded Healer” and how the paradox of someone who is broken reveals the mystery of discovering how to heal.

The retreat led me to a deeper understanding of the interior life—God lives in me and has been broken, but He also wishes to heal and be healed. Nouwen writes, “The man who articulates the movements of his inner life, who can give names to his varied experiences, needs no longer be a victim of himself, but is able to slowly and consistently remove the obstacles that prevent the spirit from entering. He is able to create space for Him whose heart is greater than his, whose eyes see more than his and whose hands can heal more than his.” Nouwen shows how naming the wounds we experience leads to the natural desire to open up to the grace of the Holy Spirit. Jesus invites us in to create that space. We see how He was an example of healing and woundedness in His ministry, being vulnerable and patient, sacrificing His life in love. We see it in His state of being God and Man, His inviting the twelve, His working miracles for the visibly and the spiritually sick, and even in His silence when He knew what was to come on the cross.

Working in ministry, I find that aiding in the healing of others comes more easily than letting myself be healed. This theme showed me how difficult it is to expose weaknesses and be vulnerable. Sometimes the simple acknowledgement of a sin or experience is overbearing. In the retreat setting I opened myself up to engage with my wounds and seek guidance in understanding what I will need to heal. I also had to recognize that the healing might not be a quick process. Words from Helen Keller, who dealt with a physical wound of blindness, showed me the wound’s potential to foster strength and growth. She wrote, “Face your deficiencies and acknowledge them; but do not let them master you. Let them teach you patience, sweetness, insight.”

We all carry wounds. In some form we react to them, hide them, or learn to mend them. One of the prayer services that concluded the retreat involved reflection on the sacrament of anointing of the sick. The leader spoke about how we do not hear about this sacrament in the way we do the joyful sacraments of first communion, confirmation or matrimony. In many ways it shows how even those who believe in the power of healing find it difficult to expose their wounds. Showing our wounds reveals a part of us that we are not proud of or afraid of knowing. How different would our world be if it seemed more acceptable to open up and anoint each other in our physical and spiritual sicknesses! In so many ways it is a privilege to be a part of that sacramental healing, to listen and allow someone to share with you what he or she is going through, or to share something yourself.

When we engage with the grace that works in our lives and look at our wounds we see how the two converge. Grace is there to help comfort and guide us in the Holy Spirit. Acknowledging the work of grace and receiving its gifts help us recognize how our wounds have the ability to make us stronger. Pope Francis spoke about embracing the wounds of Christ in others and how it transforms both them and us. “We need to touch Jesus’ wounds, caress Jesus’ wounds, bind them with tenderness; we must kiss Jesus’ wounds, literally. Just think: what happened to Saint Francis when he embraced the leper? The same thing that happened to Thomas, the Apostle: his life changed.” Our lives change when we encounter and embrace Jesus, others, and ourselves in our state of being wounded. Like the sacrament of healing, the visible act of carrying our woundedness and asking for healing leads us to better love and receive.

'

It is when I bring to mind the reality of my own fallenness and the shackling weight of sin that I am reminded of a secret weapon—one given to us as a loving gift from God. It is an old and powerful weapon forged in the fire of prayer. This essential spiritual weapon of our time is the Most Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The Rosary is a weapon of heaven’s ilk. It is the loving gaze of Heaven’s fair Maiden and at once that great “destroyer of vice” and “defeater of heresies.” It is a sinkiller. It is the battle armor against hell and all its wicked forces. And it is the end and doom of our habitual sins.

YOU MUST PRAY THE ROSARY EVERY DAY

How do I tap into this ancient power, you ask? Simple. Pray the Rosary. Pray it every day! It will kill your sin because it will draw your gaze into the holy presence of Jesus where sin cannot maintain to dwell. A mind that is steeped in temptations is a mind quickly subdued by the beauties of God’s love. The Rosary is an endeavor of God’s love, if anything. While our sin clouds the mind and the senses with the dehumanizing darkness of wayward affections, the Rosary is a journey out of that darkness. “Say the Holy Rosary. Blessed be that monotony of Hail Mary’s which purifies the monotony of your sins!” — Saint Josemaria Escriva

With each bead, each Our Father and each Hail Mary, the monotony of our prayer turns the tide against the monotony of our sins and a brilliant light begins to fire out the darkness in a soul.

THE ROSARY IS A FAITHFUL PROMISE… BUT BE NOT PROUD

According to pious tradition, Our Lady gave us fifteen promises when she gifted us the Rosary: signal graces, special protection, flourishing virtue, armor against hell, destruction of vice and the defeat of heresies, a soul that shall not perish—these are but a handful. But above all else, the Rosary is a promise of drawing near to the heart of Christ, by looking at His life through the eyes of His loving mother. When heaven makes a promise, it never does so lightly. The promises of heaven are always kept. This puts the power of heaven at your disposal to destro the enemy of your soul.

Pride will kill your desire to pray the Rosary. Many will say that they do not need it. It is boring, too time consuming—the simple and affective instrument of God’s pious and lowly. Precisely! If the Rosary is a child’s prayer, then let yourself become a child—to such belongs the kingdom of God.

THE ROSARY MYSTERIES WILL SHAPE YOUR SOUL

If you are burdened and confused by your own suffering or that which you see in the world, contemplate the passion of Our Lord in the sorrowful mysteries. If you are anxious about tomorrow and unsure of God’s power in your life, contemplate the resurrection power of God in the glorious mysteries. If you are sensing God’s call to follow Him faithfully, yet are too afraid to step out on that unknown journey, say “yes” to God with the Blessed Virgin Mary in the joyful mysteries. If you fret a great lack of inner fortitude to believe God’s words and the transforming power of the Son of Man, look to the life of Jesus in the luminous mysteries. Your soul will learn to exult in these wonderful scenes and your soul will begin to take the shape of it. This is the work of Our Lord and His most loving mother in the life of those who come to Him in prayer through the Rosary.

The Rosary is the book of the blind, where souls see and enact the greatest drama of love the world has ever known; it is the book of the simple, which initiates them into mysteries and knowledge more satisfying than the education of other men; it is the book of the aged, whose eyes close upon the shadow of this world, and open on the substance of the next. “The power of the rosary is beyond description.” — Archbishop Fulton Sheen

The Rosary is so often said in a flood of thoughts. It is hard to maintain the Gospel scenes at the forefront of the mind while one prays it. It is in this time of prayer that our worries and our joys come to the surface against the background of a holy meditation. It is the sweet background music to our lives, consoling us in times of great distress, and reminding us in times of great forgetfulness that we are never alone. The Rosary is an offering of us to holiness.

THE ROSARY IS A PATH TO VICTORY

If a particular sin plagues you and steals your joy, strike a fateful first blow against it with a faithful recitation of the Rosary. Even if you are a skeptic, take a leap of faith! Commit to pray the Rosary daily. If you do it, you will witness the manifold power of God transforming your life. Do not worry whether or not the Rosary is your only path to victory: There are many paths and many tools that are given us by God. But the Rosary is a channel that runs deep and wide. It will lead you on a path to have your greatest needs fulfilled. It is a vessel that carries you to whatever miracle you may need for your soul to find Healing.

Here is an example to help you understand the efficacy of the Rosary: “Do you remember the story of David who vanquished Goliath? What steps did the young Israelite take to overthrow the giant? He struck him in the middle of the forehead with a pebble from his sling. If we regard the Philistine as representing evil and all its powers: heresy, impurity, pride—we can consider the little stones from the sling capable of overthrowing the enemy as symbolizing the Aves of the Rosary.” —Dom Columba Marmion, “Christ, the Ideal of the Priest”

'

A quirky cartoon showed a bedraggled and disheveled prisoner probing his open cell door, calling to his gaunt cell mate, “I have some good news and bad news for you. The good news is that I just found that this cell door isn’t locked. The bad news is that all these years it never was—there’s no keyhole!” The “bad” news is the fact that countless people imprison themselves, often for years, in their self-induced guilt, and the really “bad” news is that they do not realize the “good” news that the Lord has provided an easy escape plan.

Heaven is full of sinners-turned-saints who have experienced the absurdity of that cartoon. For instance, Saint Peter Julian Eymard confessed, “After pursuing me for a long time the Lord ‘imprisoned’ me, as it were. He deprived me of everything to force me to focus on Him, but invariably I returned to the nothingness of worldly interests, shunning the abyss of His love.”

Why would anyone choose to live in a prison cell when not forced to do so? Or wallow in the sludge of oppressive, negative feelings of guilt, when a simple cleansing of the filth is almost absurdly within reach? Our heavenly Father, in His ineffably impulsive divine love, can hardly wait to “forgive us our trespasses.” The spirit-breathed inspiration of the prophet Micah articulates this amazing truth as a question for devotees of pagan gods: “Who is a God like you, pardoning iniquity and passing over the transgression?” (Micah 7:18).

Imagine a person so dysfunctional that he shuts himself up in a dark, stuffy cave, and closes the entrance so tightly that not the slightest ray of sunlight can penetrate the darkness. Would anyone blame the sun for the darkness of the cave? In response we would want to scream, “Open the entrance of the cave and let in some sunlight! Better still, come outside and bask in the brilliant warmth of this beautiful day!” The “good news” is God’s gift offered to every despondent heart: “In your presence there is fullness of joy” (Psalm 16:11).

The “Catechism of the Catholic Church” (CCC) explains how God’s loving mercy overrides His righteous indignation at the horrendous evil of sin, which is an act of insulting the Creator of the universe. “When the sinner takes the tiniest step toward His waiting open arms, he is embraced in a flood of the warmest affection from a God whose tenderness and love totals far more than all the human love added up from the beginning of human existence on earth.” Few will deny that God’s wisdom or power is infinite—although no one can really grasp it. God’s infinite mercy is a concept that many prisoners of their own guilt find hard to appreciate. As Paul says (2

Corinthians 4:4), “In their case the god of this world has blinded the minds of the unbelievers, to keep them from seeing the light of the gospel.” They cannot perform God’s simple requirement for soul freedom: “Repent and turn to God so that your sins may be wiped out” (Acts 3:19).

THE SIX PORTALS OF GOD’S MERCY

From their self-imprisonment, they may be aware of the “no-keyhole door,” but they may be unaware that their cell has a number of unlocked doors to afford them their escape from the self-confinement of sin. The Bible speaks of six such portals of God’s mercy—three of which are sacraments—but implied for each one is the prerequisite of a repentant heart.

First, of course, is the “start-off-clean” sacrament of baptism that removes original sin, which is “contracted, not committed—a state and not an act” (CCC 404), described in Romans 5:12. In the baptism of non infants, repented personal sin is also remitted: “Repent, and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven” (Acts 2:38). Second is the sacrament of reconciliation (often improperly called “confession,” which is only the penitent’s act of relating his sins to the priest). This sacrament is the most perfect “door of escape from the prison cell of sin” because it was instituted by Jesus precisely for that purpose alone. It was to be channeled only through the Apostles and their clergy successors: “As the Father has sent me, so I send you … If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained” (John 20:21-23).

Besides conferring God’s “negative mercy”—sin removal—this sacrament also confers more of God’s “positive mercy,” namely, a restoration or increase of sanctifying grace (2 Peter 1:4); a surge of actual grace to discern better what is sinful and motivation to avoid it (Philippians. 2:13); an inflow of sacramental grace that intensifies contrition (2 Corinthians 7:10); an increase of merit, i.e., heavenly reward (1 Corinthians 3:8); an added indulgence—a lessening, shortening or dissolving of accumulated purgatorial suffering (1 Corinthians 3:13-15); and, finally, a deep spiritual encounter with Christ, the Good Shepherd, in His gentle mercy (Matthew 11:28).

The third portal-sacrament of mercy is the sacrament of the anointing of the sick, formerly called “Extreme Unction.” “Are any among you sick? They should call for the elders of the church and have them pray over them, anointing them with oil in the name of the Lord … and the Lord will raise them up; and anyone who has committed sins will be forgiven” (James 5:14-15).

The fourth portal of mercy is contrition—either “perfect” (based on love of God) or “imperfect,” also called “attrition” (based on fear of punishment) (John 5:16-17)—can educe forgiveness of sin. Without sacramental confession and its many special advantages, perfect contrition by itself, even prior to confession, would suffice to remove mortal sin. However, ecclesiastical law, not divine law, requires that before receiving communion any such already-forgiven mortal sins be “submitted to the keys” of the Church’s power in the sacrament of reconciliation, if available). Meanwhile, if no confession is available, or if the sins are doubtfully mortal, communion may be received after a preparation by perfect contrition. Imperfect contrition without confession is not a sufficient preparation for communion after mortal or doubtfully mortal sin. But with a valid confession, even imperfect contrition suffices to remove any sin. All of this was affirmed by the Council of Trent.

Fifth, an act of sincere love of God would imply a deep regret at having offended Him as the beloved of the soul. This would implicitly contain an act of perfect contrition and, hence, would be conditioned on the above statements regarding perfect contrition. “I tell you, her sins, which were many, have been forgiven; hence she has shown great love. But the one to whom little is forgiven, loves little” (Luke 7:47).

Sixth, an act of sincere fraternal charity—that is, an act of love of God as His presence is recognized in another human: “We know that we have passed from death to life because we love one another. Whoever does not love abides in death” (1 John 3:14). This Christ focused fraternal charity would also implicitly contain perfect contrition and would be subject to the same conditions.

From these six routes of “escape from the prison of sin,” we can only marvel at how the Lord strives to give us every opportunity to be free of sin’s bondage and confinement. It seems that He strives to exhaust His divine ingenuity in finding ways to shower us with His loving mercy. All that is required of us is to reach out to Him to be caught up into His embrace of mercy.

A classic bumper sticker says, “If you feel far from God, guess who moved!” That is a reversible separation, as David showed in his simple prayer: “Draw near to me, redeem me, set me free” (Psalm 69:18). Yet, countless souls have become calloused by not recognizing the Lord’s yearning to embrace us and “nuzzle us to His divine cheek.” “I took them up in my arms; but they did not know that I healed them. I led them with cords of human kindness, with bands of love … like those who lift infants to their cheeks” (Hosea 11:3-4).

A passenger next to me on a flight noticed my Roman collar and soon engaged me in a conversation about religion, remarking that he had given up his childhood faith, “because,” he said, “the Bible speaks so much about the wrath of God.” He was incredulous when I told him that every such passage was qualified by the option offered to every sinner to evade such wrath by turning to God’s mercy, and that the mercy of God was mentioned in the Bible directly in more than 400 places and indirectly in hundreds of other places, from mercy parables (as in Luke 15) to psalm-prayers.

When he brought up the time-worn objection about Jesus’ referral to the “unforgivable sin,” I explained that any sin that is “unforgivable” is not unforgivable by reason of God’s refusal to forgive, but by the sinner’s refusal to be forgiven. The sinner refuses forgiveness by simply refusing to apologize to God (repentance) for spitting in His face by sin. The Lord patiently and lovingly urges the sinner to accept His divine forgiveness, but the recalcitrant sinner simply refuses to accept it. I showed my fellow passenger a statement from the “Catechism,” a copy of which, providentially, I happened to have in my valise. I urged him to read, not just the opening words of the passage but the entire paragraph. It started with the words of Jesus: “I tell you, every sin and blasphemy will be forgiven men, but the blasphemy against the Spirit will not be forgiven.” Then followed the CCC commentary: “There are no limits to the mercy of

God, but anyone who deliberately refuses to accept His mercy by repentance rejects the offer of salvation with the forgiveness of his sins. Such hardness of heart can lead to final impenitence and eternal loss” (CCC 1864). The third personality in God’s triple-personality, the Holy Spirit, acts as grace bestower. Thus, “blasphemy against the Spirit” is simply refusal to accept God’s grace of forgiveness and salvation.

I tried explaining this by a simple kindergarten-level illustration: “If you were poor and I offered you a no strings- attached gift of a million dollars and you refused it, could you blame me for selfishness or injustice? Your being deprived of the gift would have been your choice, not mine. Counterpoint that example with the passages about the “unforgivable sin,’ coupled with the inspired words of Peter: ‘The Lord is … is patient with you, not wanting any to perish, but all to come to repentance” (2 Peter 3:9).

I told this gentleman that the world’s worst sinner can be forgiven in a fraction of a second by simply saying to the Lord, with true sincerity, “I’m sorry.” Refusing to do so is the only way one can end up in hell. The unrepentant sinner says, in effect, that he is prepared to accept the endless anguish of hell rather than humble himself by opening himself to God’s mercy by a simple apology (repentance). I showed my fellow passenger that instead of distortedly emphasizing the wrath of God, he should emphasize the pride and absurdity of any sinner remaining unrepentant. The wrath of God is mentioned in the Bible only in the context of the obdurate and sustained refusal of persons or nations who snub His loving mercy. The devil knows that pride is the main roadblock to repentance and ultimately salvation. “God opposes the proud,” says James, “but gives grace to the humble … Submit yourselves therefore to God … Draw near to God, and he will draw near to you. Cleanse your hands, you sinners, and purify your hearts … Humble yourselves before the Lord, and He will exalt you” (James 4:6-10). The most profound act of the virtue of humility is a sinner’s heartfelt utterance of two simple words, “I’m sorry!” Recall Jesus’ simple but convicting parable of the publican versus the prideful Pharisee; both prayed, but only the publican’s humble prayer for mercy was answered.

I explained to my seat companion that the God from whom we have distanced ourselves will make a thousand steps toward us if we will only make the first step toward Him. That is what James means in stating, “Draw near to God and He will draw near to you.” It is the best scriptural answer to the poignant bumper sticker question: “If you feel far from God, guess who moved!”

When I opened my Bible and showed him just a few descriptions of God’s tender mercy, such as the parable about the Prodigal Son, his acrimony seemed to melt. I invited him to say, “I’m truly sorry, Lord”—while accepting his salvation earned for him by Jesus’ death. He hastened to blurt out that commitment—almost tearfully. His parting words were words of gratitude and a promise to return to the practice of his Christian faith. By his response to God’s grace he had changed in a moment from reprobate to righteous. Truly, “the hope of the righteous ends in gladness” (Proverbs 10:28).

This encounter left me with a grateful heart as well, as I recalled the words of James 5:20: “Whoever brings back a sinner from wandering will save the sinner’s soul from death and will cover a multitude of [his own] sins.” I had simply shown him that his prison cell of guilt had never been locked. By the nudge of the awesome mercy of God he had only to open the unlocked door and find himself free—and “if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed” (John 8:36).

'